The Story, Song of the Sea, Unfolds

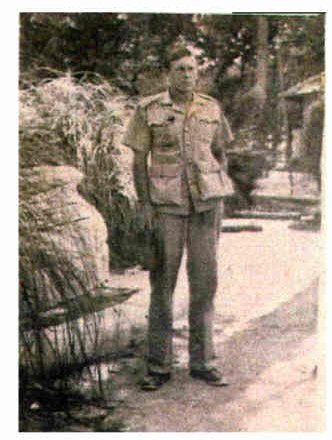

The above pictures are of mum, dad, and present cat, Charisma. Dad, Leonard Charles Cattier, was serving in the Royal Air force as a ground engineer during the 2nd World War. Mum was a fully trained Red Cross nurse, helping out during the bomb raids by Hitler in London; when the air raid sirens went off, she left her place of work to tend the injured ....her father was a doctor and mother a midwife and laid out bodies before the war.

Early Morning Memories

Mist shrouded Vales overlook the Glen,

The sun rises out of the smoky mist

Giving rise to a ghostly glimmer of hope.

Welcome to a new born day!

Spirits rising with every brightened ray,

Love a-freshened amidst the misty scene,

A new arc approaches the mind,

Yesterdays sorrow just a glimpse behind.

Memories embedded in the deepened soul entrined,

Tormented by the passages of time,

Depending on circulating circumstances

To rise to the surface again.

Chapter 1

Entering the World

An isolated cottage outside the small village of Felmersham, situated some way outside the town of Bedford , served as my birth place. I was dramatically and prematurely introduced to a war torn world on the 20th. November 1944: my parents, Ivy Ethel Melinda and Charles Leonard Cattier, weren't expecting me to arrive for another month, so I must have mirrored the unpredictably and transientness of the time which everybody was trying to survive amidst ration books and food shortages.

This was the time when Hitler was struggling to keep his power and was having a last exigency in blitzing London and parts of Southern England. V.1 "flying" bombs, commonly known as "doodle bugs", and V2 rockets which were swift and silent and resembled the Iraqui Scud missiles, were now being used by Hitler. One such rocket landed in Chelmsford, Essex. This also was a time when man's inhumanity to his fellow man had reached an all time peak in the world's "civilised" history.

My mother had been evacuated to this very remote picturesque part of the English countryside with my father's parents, his sister Violet and their two children, at a time when families were parted and children were taken from war torn London to reside in "safe" havens out in the country. Ernest, Violet’s husband, was stationed in Egypt, and helped with the everyday expenses. Vi supplemented this income by working from home, making dresses for the local Ladies. She was able to charge them a guinea, £1. 2s 6p, a dress, which was a good rate then.

.

Page 2

My father fortunately was on leave from the Royal Air force, serving during the 2nd. World War. The doctor told him that he, the doctor, and the mid-wife could not handle the birth on their own, and would he, my father, go and phone his partner. The phone was about three hundred yards down the lane, and the nearest neighbour was some distance away; there was only one house between the cottage and the small village of Felmersham.

Before his partner arrived the doctor delivered me: he was, fortunately for my mother and me, a good gynaecologist although he was known to drink. I was in breach position and a leg was caught. An half an hour had now passed, and this starved me of oxygen and I was black and blue and jaundiced .

“Don't worry, Mrs. Cattier, you have not given birth to a Chinese baby.” joked Dr. Stewart on handing me to my mother.

"I have now got to see Gypsy Rose down the lane, near here. She never has any trouble giving birth because she chews raspberry leaves!" chipped in nurse Banford, the midwife.

The next day I was being looked after by my grandfather whilst the rest of the family were going about their daily duties, when I suddenly vomited up a load of birth matter that I had collected in my system during the delivery:

"It was a frightening experience, Janet could have choked and died", my grandfather related afterwards. "I just did not know what to do, and called out for help!"

The winter progressed and my father was sent to Cyprus, Egypt, and Palestine. The war with Europe was coming to a close and this meant him entering the Japanese war in Rangoon if the Americans had not developed and dropped the Atomic bomb on Horishima and Navasaki. During the first year of my birth in l945, like many other children at this time, I may have lost my father; killed in service to his fellow man. He was a reserve pilot, and was to lose his best friend, an A1 fighter pilot, during an air raid over Germany; hit by a sniper on returning.

page 3

It is a good thing my mother was strong. She trained to be a fully qualified Red Cross nurse, attending the injured during the blitz, and was first aider and A.R.P. in the firm, where she worked. She had passed the highest Red Cross First Aid exam, and was assigned to the Markhouse Road, Walthamstow, air-raid shelter, situated near St. Saviours Church about a third of the way down, during the blitz in London; it was equipped with an operating theatre. Near there, in Lea bridge Road, at the top of Markhouse Road, there was a terrifying direct hit on a bus by a parachute bomb during an air raid. My mother had to leave her work place to go to her post that morning as soon as she heard the siren go off. During the air raids, she went home to her flat in her mother's house in Gold Smith Road, Leyton, to change into her nurses uniform and then ventured out, sidling close to the buildings in order to avoid flying debris, surreptitiously making her way to her first aid post in Markhouse Road. It was during the above direct hit on the bus that she arrived home to find her mother dead from a stroke brought on by the resumption of the air raids after a lull: "I wont survive if the raids start again." Ivy's mother Ethel Melinda Flay had told her daughter earlier.

The 'flying' bombs' as well as the parachute bombs, were being sent over by Hitler at this time. These bombs, 'Doodle Bugs', had wings on them and went silent when they stopped and started to descend. This was an horrifying situation for anyone underneath one of these bombs, knowing that silence was going to kill them. It was the more destructive type parachute bomb that hit the Markhouse Road bus full of morning shoppers: an acquaintance of mine told me the story told by his father who was an eye witness to the carnage caused by these bombs:

Leonard Charles Cattier

in Cyprus during the 2nd World War.

Ivy Ethel Melinda Cattier

Copyright©2014. All rights reserved.

These were very perilous and turbulent times indeed. Fathers, brothers, cousins, sons and friends were dying in their multitudes, and the care of the sick and needy, including the pregnant woman, was haphazard at this turbulent time. Children were evacuted, sent to safe havens out in the country, often without their parents. What truama this was going to cause them in later life was anybody's guess. In fact, it was every man for himself, and any sort of common decency was often forgotten, for every resource was put to use in fighting for "King and Country".

The cottage had no running water. It had to be pumped from a well about a hundred yards down the lane and painstakingly carried in buckets. Logs were collected for the fire and cooking stove during that extremely cold winter. I can vividly visualise my heavily pregnant mother and her family outside that cottage chopping wood under the most arduous and punishing conditions.

When the time had come for my mother to give birth, the mid-wife was called. She immediately sensed that there was something seriously wrong, and called for the doctor. My mother had been to the hospital earlier that day, and doctor King had sent her home having told her that everything was alright. But my mother had always felt my head high under her ribs and should have been kept in hospital for the birth.

. "My father was cycling down Lea bridge road at the top of Markhouse Road toward the Bakers Arms, and for some reason decided not to stop at the crossing by the Savoy Cinema. As he peddled on, he heard a terrible explosion behind him. If he had stopped at the crossing he would have been killed - as it was, he was thrown off his bike as the parachute bomb exploded behind him. Looking back, he saw that there had been a direct hit on the double decker trolley buses and the resulting carnage. Later, he happened to walk past the Leyton trolley bus depot at the Bakers Arms and, inside, he saw about three buses covered in blood."

This is the original which I am editing. Time is of the 'essence', as the saying goes...at first I changed the names, but decided this was too confusing and am using their real names in most cases. My mother tried to get me to change the names: she was such a sweet and loving person. but I cannot see the point. If you read the following, you will see the problem I was having.

Chapter 1

Entering the World

An isolated cottage, situated some way outside the small village of Felmersham, Bedford, served as my birthing place being prematurely introduced to a war torn world on the 20th. November 1944. My parents, Ivy Ethel Melinda and Charles Leonard Collier, were'nt expecting me to arrive for another month, so I must have mirrored the unpredictability and transientness of the time which everybody was trying to survive, amidst ration books and food shortages.

This was the time Hitler was struggling to keep his power and was having a last exigency of action in blitzing London and parts of the South of England. Vl "flying" bombs, commonly known as "doodle bugs", and V2 rockets, which were very swift and silent, and resembled the Iraqui "Scud" missiles, were now being sent over; one such rocket landed in Chelmsford, Essex. This also was a time when man's inhumanity to his fellow man had reached an all time peak in the world's "civilized" history.

My mother had been evacuated to this very remote picturesque part of the English countryside with my father's parents, his sister Violet, whose husband Ernest was in Egypt and sent money to her to help with the expenses, and their three children, at a time when families were parted and children were taken from war torn London to reside in "safe" havens out in the country. Fathers, brothers, cousins, son's and friends were dying in their multitudes, and the care of the sick and needy, including the pregnant woman, was almost none existent at this turbulent time. It was every man for himself, and any sort of common decency was often forgotten, for every resource was put to use in fighting for "King and Country".

The cottage had no running water; it had to be pumped from a well about a hundred yards down the lane and painstakenly carried in buckets. Logs were collected for the for the fire and stove during that extremely cold winter, and I can vividly visualise my mother and her family outside the cottage chopping wood under the most arduous conditions.

When the time had come for my mother to give birth, the mid-wife was called. She immediately sensed that there was something seriously wrong, and called for the doctor.

My father, who was on leave from the Royal Airforce, in which he was serving during the 2nd. World War, was told by the doctor that he and the mid-wife could not handle the birth on their own, and would he, my father, go and phone his partner. The phone was down the lane, and the nearest neighbour was some distance away; there was only one house between the cottage and the small village of Felmersham.

Before his partner arrived the doctor, who was, fortunately for my mother and me, a good gynaecologist, had delivered me. I was in breach position and had a leg caught. An half an hour had now passed, and this was enough to starve me of oxygen. I was black and blue down my right side, and jaundiced .

“Do not worry, Mrs. Collier, you have not given birth to a Chinese baby!”? joked Dr. Stewart on handing me to my mother.

The next day, while I was being looked after by my grandfather, while the rest of the family were going about their daily duties, I suddenly vomited up a load of matter I had collected in the birth channel during the delivery:

"It was a frightening experience, Janine could have choked and died. " my grandfather related afterwards. "I just did not know what to do, and could only call for help."

While all this was going on, the winter was progressing, and the war continuing. My father was sent to Cyprus, Egypt and Palestine. The war with Europe was coming to a close and this would have meant him entering the Japanese war at Rangoon, if the A bomb had not been dropped on Horishima, Japan, during the first year of my birth in l945. Like many other children at this time, I may have lost my father during the war.

It is a good thing my mother was strong. She was in the Red Cross and was first aider and A.R.P. in the firm, where she worked. She had passed the Red Cross First Aid exam, and was assigned to the Markhouse Road, Walthamstow, air-raid shelter, situated near St. Saviours Church about a third of the way down, during the blitz in London; it was equipped with an operating theatre. Near here, in Lea bridge Road, at the top of Markhouse Road, there was a direct hit on a bus, or buses, by a parachute bomb, during an air raid. My mother, during this raid, left her work place to go to her post that morning as soon as she heard the siren go off. During the air raids, she went home to her flat in her mother's house in Gold Smith Road, Leyton, to change into her nurses uniform and then venture out, sidling close to the buildings in order to avoid flying debris, surreptitiously making her way to her first aid post in Markhouse Road. It was during the above direct hit on the bus that she arrived home to find her mother dead. The "flying bombs", as well as the parachute bombs, were being sent over by Hitler at this time. The "Doogle Bugs" had wings on them and went silent when they stopped and started to descend; this was horrifying for anyone underneath one knowing that silence was going to kill them. It was the more destructive type parachute bomb that hit the buses full of morning shoppers. An acquaintance of mine told me the story of his father;

"My father was cycling down Lea bridge road at the top of Markhouse Road toward the Bakers Arms, and for some reason decided not to stop at the crossing by the Savoy Cinema. As he peddled on, he heard a terrible explosion behind him. If he had stopped at the crossing he would have been killed - as it was, he got thrown off his bike as the parachute bomb exploded behind him. Looking back, he saw that there had been a direct hit on the double decker trolley buses and the resulting carnage. Later, I happened to walk past the Leyton trolley bus depot at the Bakers Arms and, inside, I saw about three buses covered in blood."

Ivy's mother, just before she died, had said to her daughter earlier:

"If the air raids start up again I will not be able to stand it. I have had enough of this war." There had been a lull in the raids, as Hitler's power was diminishing in Europe.

Ivy's parents had lived in Atherton Road, Forest Gate, and in their later years, in Goldsmith Road, Leyton. Her father had been an herbalist and skin specialist and had had a consulting room in Atherton Road, with a notice outside his front door "Herbalist and Skin Specialist". He would some times sell his medicines on a stall down the local market where he pulled teeth as well. He would attract the custom by throwing a sword high into the air, catching it with one hand. It went through his hand one day! If he noticed any members of his family in the crowd that gathered round him, he would call them up onto his platform and pretend that they were members of the public, in order to display his medical skill and bandaging on them. My father-in-law, Douglas, once related to me:

"My mother had a greengrocery stall down the market, and when I was a very young boy, before the war, I used to see this man throw this sword high into the air and catch it. It would glint in the sun, and one could observe it a long way off flying above the crowds. You always knew he was there! There was another man who had an one wheel cycle, and would entertain the crowds by doing acrobats on it. Talented stall-holders did this sort of thing, in those days, to attract the attention of potential customers."

One day, my mother's mother was asked by my grandfather:

"Will you pull out five scull teeth so that I can show a sparkling white smile. This will be good for business.!"

"This was a time I got my own back on him, and repaid him for all those times he left me to bring up the children on my own while he went off to fight in another country's war; the old war monger! I sat him down in our kitchen chair and yanked out his teeth. I made sure he felt it!" Ivy's mother told her daughter jokingly. Ivy's father, Albert, had fought in the First World War and was a commando in the Boar War, where he received the Commonwealth Medal. He rose from a young private to Sergeant Major, M.0. and was mentioned in dispatches for bravery during the First World War. Albert refused a medal during this war because "My men did as much as me". Belinda Seckers parents disowned her for marrying Albert when he was just a private, because he did not hold a high enough rank in the army.

Ivy Ethel Melinda had come to live with her mother, Belinda Ethel Melinda when she was nearly fourteen and ready to go out to work; my mother had been given my grandmother's middle two Christian names for her middle names. She had been farmed out to various foster parents since she was born, because her mother was too ill to look after her. Therefore, Ivy hardly knew her parents. At least, not in the same way that her eight brothers and sister had known them. She had four surviving brothers and one sister.

Ivy's father died during the war, at the age of seventy, as the result of parkingson's disease, brought on by the coke fires when he worked in his latter life as a fire watchman during the blitz of London. He wanted to enter the war, but the M.O.D told him he was too old to fight.

Six months prior to his death, my grandmother had taken an insurance policy out on her husband;

"I would take a lease out on that man's life." the insurance man had said to his partner, the man standing next to him, as he observed Belinda's tall, moustached, doctor-like, buttonholed, husband strolling down the road towards them, on his way home from work. In my opinion, my grandfather should have retired, but knowing my mother's side of the family, as I do now, not any of them do! My uncle Valentine, a police inspector - he had a college education paid by my grandfather, and became one of the youngest police inspectors in the Metropolitan Police Force during that time - was not the exception.

On retiring from the Metropolitan Police, Valentine bought a small holding in Cornwall. He put cut flowers, which he had grown, for sale on a stall with an "honesty" box, by the entrance to his garden; he then hid and arrested people if they did not pay for them!

I never met my uncle Valentine owing to some friction between him and my mother. I have never met his children, my cousins Brian and Dennis. Brian became a maths master and, I believe, a headmaster of a private school. Dennis owns his own business.

My mother often stayed with Valentine and his family when she was small. On one occasion when they all went on holiday to Cornwall by car, Dennis could not be found in the back seat. The family found the car door swinging open and Dennis sitting in middle of the road some while back.

Valentine's wife was a classic beauty, with long blond hair she could sit on. When, sadly, she died, while the boys were quite young, with the consequence that everyone was heart broken; Valentine never entirely got over her. Corrine, I shall call her, spoke well and taught my mother good etiquette in how to lay the table properly, etc.

Valentine married again; a nurse who had nursed him back to health after the death of Corrine had convinced him he should get on with his life again. "Mr. O'niel, you have got to pull yourself together and get on with your life." she chided him in the convalescent home where he ended up after a break down in his health due to his wife's death. She was his nurse.

Both my parents were keen cyclists, belonging to cycling clubs and had entered racing competitions. I expect they had hoped I would follow in their footsteps. Owing to my disability, they could see I would be unable to do so. They felt they would have to carry me for the rest of their lives. I was determined that this would not be the case!

The hospital, where my mother had had just one ante-natal check up, was obviously wrong in saying everything was fine with the pregnancy, and that the head was engaged, and that she had four weeks to go. My mother could always feel my head high under her rib cage. If this hospital had made that kind of mistake today, it would certainly have been made to pay compensation. In one such recent case, due to the neglect of the hospital, the recipient, a cerebral palsy victim, was awarded one million pounds in compensation. This should make expectant mothers to-day appreciate the care and attention hospitals give to their patients today.

Although I was given excellent care when pregnant with my daughter, I do have one bone of contention to relate, that could have led to tragic circumstances for me and my baby daughter. I am sure this was because I had refused a blood transfusion, and the midwife had not set eyes on me before; I had only seen the doctor, during my ante-natal visits to the hospital:-

Because I was sticking to my belief, in that God's Word forbids blood transfusions - "do not eat any kind of blood..... good health to you", - the mid wife turned on me.

On arriving at King Georges Hospital Hospital, Ilford at eleven pm having been taken there by car, driven by my mother with my husband Desmond in the front passenger seat, I was greeted by a lone midwife after ringing the bell at the main entrance. The contactions were getting more frequent by this time, but I felt quite confident that I would have a good birth, as I had been to a chiropractor, and had been taking raspberry leaf tea, recommended by a lady in my Church. Also, my mother told me a story that her midwife had related to her after I had been born in that village of Felmersham in Bedford:

" Tomorrow, I am going to deliver gypsy Rose's baby, who lives near the village. She never has any difficulty giving birth. She eats raspberry leaves.! She has a brood of children."

The midwife at King Georges Maternity Hospital took us inside and motioned to my mother and husband to go home. The hospital had a ghostly appearance and no one else was in evidence. She directed me to a side room and instructed me to get undressed. I had not seen her in my ante-natal checkups, having only seen the doctor.

When I was ready, and sitting on the bed, the mid-wife came in. She looked huge in her old fashioned grey nurses uniform with black cardigan and frilly white cap. She must have weighed at least twenty stone. She had a kind looking little nurse with her, who was holding a tray of syringes and other paraphernalia.

"I want you to have this injection, to put you and the baby to sleep. You are down to see the doctor, and he is only available in the morning. I was horrified. This was the very thing that a friend of mine had told me that I should not agree to. She had been put to sleep in that same hospital, and her little boy was born by forcep; as a consequence he developed a speech defect.

"I do not want to be put to sleep. My baby is on it's way and I do not want it artificially delayed." I said. The midwife became angry and tried to force the injection on me. I kicked her hand away.

By this time my waters had broken and I was bleeding. As the midwife and nurse had left me on my own, I pressed the "panic" button beside my small bed in that small side room. I can remember I had been left naked with no covers over me. They entered the room, with the little nurse carrying a jug of water. All I can say, it was a scene from a concentration camp in Nazi Germany. I have written a poem about it, since.

Suddenly the midwife got angry and demanded the nurse to leave the room. The little nurse had only just put the jug down on the locker beside me, and had held out her hand in sympathy at the pain I was going through; I had even refused painkillers, in case they harmed my baby. With the exit of the kind nurse, I was left to the mercy of the midwife.

Suddenly the bed moved and I felt myself being wheeled into the delivery room by a very cantankerous midwife, who had got rid of any assistance. I could hear her muttering to herself, but could not make out what she was saying.

All of a sudden the bed-trolley stopped, and she leant over me and pushed my knees into my chest:

"Push!" she said her eyes popping out of her huge skull "You don't want a blood transfusion, so push, or you are going to die." she said glaring hatefully at me.

I did not feel frightened, as my faith in God was strong at this time, just as it is as at any other time, and I was praying that she would not do my baby any harm. I had no chance to do my breathing exercises I had learnt in anti-natal classes, and I was not given gas and air. She gave every appearance of being a wardress in one of Hitler's Nazi concentration camps!

I felt the baby enter into the world. It sounded as if she went "plop" onto a table. Goodness knows what I was lying on. The room was in darkness, except for a light under which the midwife was working. Even though I was lying on my back, I tried to see what the mid-wife was doing and found the light shone in my eyes, nearly blinding me. The midwife showed me a pair of scissors and said nastily, that she was going to cut me, and after she had delivered my baby, I could see her threading a needle, ready to sew me up.

When I moved to Felchester I found out that the hospitals there had given up the practice of making incisions to the neck of the womb, years ago. I went on to suffer from several D&C. operations as a direct result of this seemingly malpractice, and had difficulty with walking.

When I knew all danger to my baby had passed the baby had been delivered, I asked for a pain killing injection.

"Now you want an injection!" said the midwife unsympathetically, stabbing the needle into my thigh. With those last words ringing in my ears and the pain from that needle, I promptly fell asleep.

I did not wake until gone eight that morning and promptly phoned home to tell the family that the new addition was an eight pound, one ounce baby girl who was introduced to the world at 4.20 that morning, although I had not seen or held her yet.

Because breast milk is best for new born babies, I was determined to feed Audery myself, and the day midwife's extreme kindness partially made up for the cruel approach of the delivery midwife, who had been round that morning and made a point of chatting to the woman in the next but one bed to me. She just stalked past my bed, ignoring me and my baby daughter.

As I did not want the fuss and did not want to detract from the happy event of my "perfect" daughter entering into the world, I did not feel compelled to put in a complaint about the irate behaviour of the delivery night-shift mid-wife.

Although I was breast feeding my baby, the hospital staff gave her a milk supplement as well, and I did not see reason to contest this. Those nurses worked really hard; I was always the last mother in that ward to settle down to sleep at night. Being so happy, I sang quietly to little Audrey at every opportunity. Sometimes it was eleven p.m. before I finished feeding her, and after handing her to one of the nurses, I would not see her until the next morning.

The kind day-shift nurses had put me in a quiet corner by the window and I was showered with gifts and flowers from the people in my church, The Bible Society. One such family had even given me a cot and I had known the wife's young sister Marilyn, who was deaf, since my early school days. I also had a large bunch of flowers from the Wingfield Music Club.

When my mother came to collect me at the end if my eight day stay in that maternity hospital, (my husband couldn't collect me as he was then a school teacher, busy in a school teaching) she was told by one of the nurses:

"Your daughter has done very well, but she will need a lot of help!" and then added with wise intent in her voice, after looking at my bright eyed baby, who appeared to be very contented and smiling whilst being held in my mother's arms: "That isn't wind that's making her do that; that is a real smile!" Those nurses had spent a lot of time helping me in that ward, and I thanked them profusely, forgetting the horrible midwife who had delivered my daughter.

.

Although I was a bonny baby, which was largely due to the loving care of my mother, my paternal grandmother, and my father’s sister Violet, I did not start to walk until I was two and a half years of age. My legs were very weak, and thin by now.

They patientlly put me against the living room wall and was constantly told to take some steps until gradually I got the idea. My parents had gone on a short weekend break on their bikes, and by the time they came home, they were thrilled to see that their disabled daughter had taken her first three steps.

Chapter 2

My Father

My mother had married my father two years prior to my birth; they had met when he was eighteen and an air cadet living in Whipps Cross Walthamstow. He had been born to Allice and Henry, "Harry", Collier in a flat near London Fields, Dalston. He had a sister, Violet and a brother Henry.

There had been another sister, Gladis, who had tragically died during the dipheria scourge after the First World War. My Grandmother, Alice Dennis - she preferred to use her maiden name for reasons that puzzle me, probably because it was french and was frightened of reprisals- had called the doctor to her ailing child. He diagnosed tonsilitis, even though dipheria was rampant in the area, and had left the child to die within that week. If that negligent docter had taken a swab from the girls throat and tested it for the dipheria bacillus, Gladis' life would, no doubt, have been saved.

In the Cadets, Charles was principle cavalry trumpeter, and played all the solo parts, including sundown. He had previously brought home a violin from school, but his mother Alice would not spend money on music lessons, even though her husband, Harry, was bringing a fair wage as a French polisher.

"I am not paying for something that will be useless when you leave School" said Alice " I have said the same thing to your brother. Music is useless for getting employment."

My father was the youngest of Alice's children, and she wanted him to become a policeman on completing his schooling. She change her mind, in latter years, as she contemplated the dangers that "Her Charles" would encounter in such employment. That is why my father became an apprentice in the Lithographic Printing world on finishing school. His apprenticeship was interrupted when the war broke out and he was conscripted into the Royal Air Force. He was learning to be a proper musician in the Air Cadets, and even this was swept away from him due to the onset of the second world war.

Charles married my mother on the twelfth of December, l942, after he was sent to the Middle East, and I was born to them nearly two years later. Ivy had to borrow a wedding dress from one of her friends, as it was difficult by luxuriant articles in this critical period of the twentieth century, owing to the rationing of food and clothes. Also money was scarce during this time. Thousands of brave young men were sent to fight for their "King and Country" after being promised houses and jobs when Hitler was demobilised and the war over. History shows that this was a false promise. There were no houses to come home to, and jobs were scarce, although there had been full employment during the war period. Britain had been lifted out of the depression of the nineteen thirties by the mass production war merchandise, which came to a halt as soon as the war ended. Britain was slow in getting the rebuilding of houses and the blitzted towns underway, as most of the skilled labourers had succumbed to the attrocities of the militant egressions and martial combats.

My mother and father had to struggle to make ends meet after he was demobbed, with Charles finishing his apprenticeship, on an apprentices wages.

My father was away in the Middle East until he was demobbed in l947. Nearly three years had now passed since I was born, and when he came home from there, he was a total stranger to me, and I distinctly remember hiding under the dining room table each evening he came home from work, kicking and lashing out at the wheel of his bicycle, stuttering loudly “Angor! Bagor!" and struggled in my head to add; "Go away!" Everyone must have been surprised that I could say the former two words quite easily. I did this for a long time after he was demobbed from the Royal Airforce, in which he had served seven long years. I had accepted my dad's sister's husband Ernest, my godfather, as my father, as he had came home from the war not long after I was born. He was a cabinet maker by trade, and was assigned, while he was in Egypt, to making officers beds, and sent money home to his family.

Now I feel bad about not accepting my poor father during those intitial years, especially as he sustained a back injury on a visit to Egypt for the cycle race there while waiting to be mobilized into the Japanese War at Rangoon, and I might not have seen him again! He could have been involved in the fighting and killed, like many of his friends. One such friend was a bomber pilot, and on rare occasions "flagged" the two cottages, which was an air man's symbol of a greeting, by flying low over them. Both he and my father were under General "Bomber" Harris stationed at the Bedfordshire Royal Airforce Base. Unfortunately, this friend never returned during one of the Battle of Britain air raids on Germany. He had been hit by a sniper enemy aircraft.

These two cottages, where my mother, because she was pregnant, was evacuated with my father's family, were situated in the depths of the picturesque Bedfordshire countryside and had exceedingly meagre amenities; there was a mother and son living in the first of these cottages. There was a field with horses on it opposite and they often poked their curious heads over the fence for tip bits.

There was an American Air Base stationed nearby, and Ivy could hear the torrid gossip, concerning the American airmen and the local girls - who would do anything for a pair of nylon stockings! - when she went shopping in the nearby village with the ration books for the family's provisions. Mrs. White's grocery store was virtually a meeting place for the conscientious married woman and therefore a hive interesting titillating conversation about the "goings ons" at the Air Base. Hence the saying of the American presence in this country: "Overpaid, oversexed and over here!"

This rather unpleasant situation was one of the reasons my mother decided to leave the "security" of the family evacuation home in Bedfordshire to return to the turbulent atmosphere of war torn London and rent a bedsit in Leyonstone. Another, and more poignant and appropriate reason, was that my father's work, lithographic printing, would require a move to that area.

It was there in this one roomed bedsit, during the final part of the war, I picked up all the childhood illnesses, including whooping cough, chicken pox and measles, which must have been responsible for my type of deafness - I hear men's voices better than womens. Ivy's landlady suffered from St. Vitus'sDance - a disorder of the nervous system in which the afflicted person is always fidgeting - and was not a clean person.

A few years later, when I was just about walking and on a visit with my mother to a doctor's surgery, some ignorant person thought I was afflicted with this complaint, as due to the type of cerebral palsy I had I was unable to sit still on my seat:

"Has that child got St. Vitus's Dance?" a woman asked my vexed mother, who was doing her best to keep, me, her active minded palsied, youngster, glued to the seat. The boy in my mother's rented accommodation was always leaning over my pram and breathing over me. Once my mother shook the hallway mat, and a load of dust enveloped her!

In Bedfordshire, there had been an outbreak of polio, and the dirty River Ouze nearby the cottages, helped to perpetuate this disease, as the local children often swam in it. A boy was found collapsed with the virus in a field near the cottage, and had only the previous day been breathing over my pram at my cousin Valerie's birthday party; she was two years old. So, perhaps I did contract polio here, as the medical profession found that I was already immune from the disease when I applied for vaccination when I was twelve years old. Anyhow, perhaps it was for the best that my mother did move to London during the height of the air-raids.

Owing to measles - I can remember being in terrible pain and screaming the night away in my cot, in that bedsit in Leyton with an huge abscess in each of my ears which eventually burst damaging the inner ear, leaving with the predicament of hearing low sounds better than high sounds. A recent hearing graph that was done at the Felchester Hospital, shows the whole middle range, the speech area, practically missing. It also showed that both ears have the same hearing loss.

Chapter 3

Starting School

It will always seem strange, to me, that my deafness was not discovered until I was eleven years old. I was constantly getting hit at my primary school for things I did not know I had done. One instance was, the time on my first day at infants school in Gamuel Road, Walthamstow, the teacher, Miss Pitmus had told us sternly;

"Nobody should come down the slide headfirst! Anyone doing so will be punished." Of course, not hearing her command in the school playground, where they had rabbit hatches, slides, and swings, I appeared to have disobeyed her order, by climbing the slide steps in front of the lined up children and doing that very forbidden exercise - although very unsteady on my legs, my brain being very alert and crystal clear, I had worked out how I could do it. Also my mind had not yet been trained to concentrate on the person's lips as they were talking. I later worked this technique out without having any help, and was able to disguise my acute deafness.

"I had just told the class not to use the slide, and madam immediately goes up the steps and comes down head first." Miss Pitmus later related to my mother on one of the occasions she picked me up after school. Miss Pitmus became well beloved of me, because she seemed to understand me. She even allowed me to come to school in my cowgirl suit and on my three wheel bike, which I called my "horse" and tied it up outside my classroom.

"I do not mind how Janine comes to school, as long as she attends." she remarked to my astounded mother. She often sat me on her knee and lifted me up to introduce me to school V.I.P. visitors and the school governers .

"Janine would never have had to leave this school if I could have taught her through the coming years." Miss Pitmus told my worried parents when I had decided to leave her school when I entered Miss Tobin's class, the next year who used to pick on me in assembly dragging me out for talking. I had also to cope with bullying from the deprived children, who became jealous of us kids whose father's survived the war and theirs had not. Twice I had been knocked unconscious in the school playground during normal playtime activities. I can remember huge motor tyre wheels being store in the school playground which the children were allowed to wheel about - consequently wheeling them at each other, so I never stood a chance on my legs.

When my mother had first brought me to the school at the age of five to meet the headmistress - my friends having stated at four and a half - I wondered off out of the study while they were talking, and disappeared. After a lengthy search of the school building, the Headmistress and my mother heard loud laughter coming from the playground. On investigating the uproar, they found the source of the mirth was in the direction of the rabbit hatches. There they found me crouched underneath the hatches with the whole school pointing and laughing. My mother has never let me forget that embarrassing day!

My parents, by this time, had settled in Walthamstow in a little terraced house that my mother had obtained with a down payment of a five pounds retaining fee, beating another would be purchaser by a slieght of the hand, in other words got there first! Then came the main deposit from the proceeds of her mother's will.

Ivy's mother had died of a stroke when my mother was three months pregnant with me. Even though her mother had told her, because she was the only one who had looked after her in her very sick months, she could have anything she wished in the house if anything happened to her, Ivy hardly got anything and had to leave her nice flat in the house in Goldsmith Road, as the conditions of the will were that the proceeds from the estate had to be divided equally between the eight surviving children. The second eldest brother, Val, whom I have spoken of earlier in this chapter, who was an inspector with the Metropolitan police, had written to my mother warning her not to touch anything until he was free to come and sort out the estate. This upset my mother and prompted my father's sister to write to Valentine, the brother, telling him off for upsetting a pregnant woman.

My mother had to stay the night on her own with her dead mother whom she had laid out for the undertakers,that day, in the downstairs front room. This was the way of most families lived during the war.

The same night Ivy had gone to bed frightened, Charles had obtained leave and came to visit his wife not knowing her mother was dead, and thinking that everybody was asleep, climbed through an unlocked front room window - nobody thought of locking their windows as they do today, as burglary was virtually unheard of in that area. He felt around the couch and felt something cold. He had inadvertantly come across Ivy's dead mother.

Chapter 4

Bert Lyon's music venture.

Herbert Lyon came to Hale End Rd., Open Air School for the physically disabled during l953. and I was approximately eight years old by this time. Mr. Lyon, who played the violin, desired to give handicapped children the opportunity to learn music, as he had seen many disabled children in Egypt during the war and became determined to something about the lot of the disabled after he became demobbed. He was also disabled during the previous year of 1952, having had three fingers sewn back on after an accident to his left hand with a machine in a joinery factory where he worked. His wife, Lily, was a competent secretary and musician, playing both piano and cello, even though she was hard of hearing in which she could hear high sounds better than low sounds; the opposite to my hearing type.

“Uncle Bert”, as he eventually became known to us children, told me that before he had his accident, he had played duets with Stephane Grappelli and played in symphony orchestras. It was the one he joined in Leyton after leaving Egypt when the war ended, where he was destined to meet his future wife. He had had trouble with a piece of music and Lillian had offered to help him and the friendship that followed resulted in marriage.

The accident proved to be to Bert’s advantage, as he was able to register disabled and obtain better employment as an Insurance Agent. I wish it had been as easy for me to find work by registering, as I found better employment when I did not register. All my jobs were obtained in this way. Instead of being one of a workforce of two per. cent of disabled workers - and my disability made more obvious - I was competing with a work force of so called ninety eight per. cent able bodied workers and found I did not have the indignity of having to explain "What is wrong with you?" and obtained some really excellent jobs. I believe the reason for this paradox was the fact that I had a duel disability, and was highly intelligent with it. The employer would only be interested in my disability, and not become aware of what I could do. The only time I had registered disabled, I was given my green card back after a two week period; cruelly being told by two solemn emotionless middle aged women that I was unsuitable. I tore that card up and swore I would never register again.

Owing to the fact that the able bodied schools in the area I lived were rough and ill equipped for disabled children, I decided to attend Hale End Rd. School School for the physically disabled, which Bert, some months later, re-named Wingfield House. This was to prove a prodigious move for me.

"The handicapped schools should have a proper name like able-bodied schools, and should have the opportunities to learn as ablebodied schools." Bert insisted. "When a child is asked what school he or she attends, they should be able to give a proper name for it and be proud of their school."

At first, it was a relaxing novelty to be picked up for school by a school bus every day and brought home to my door as previously I had to walk some distance with the ensuing mimic taking as I passed the prefabs in Longfellow Road.

Our bus lady, Mrs. Redford, pushed, jostled, and bullied some of the children and was always picking on one, or the other of us, and this was to have a dire a dire affect on my psych later on in my life. She turned out a real psychological bully and had turned her sadistic ways on me.

At this time I was very weak on my legs and was bullied outside my primary school, in Gamuel Road, Walthamstow; therefore I was glad to change schools and had done I did so entirely of my own volition as I was knocked unconscious twice in the playground during normal playtime activities. Another factor that lead to my decision to change schools was Queens Road Park, situated outside our school; their were undesirables, men, etc., waiting in it for us kids to come out of the school gates, and pass by. My friend, Christine, one of a set of twins who guarded me, ended up having stitches to a wound in her head caused by a brick thrown from a bomb damage site, which had not been fenced off, outside the school next to the back of the Park which extended from Queens Road to Longfellow Road, parrallel to Markhouse Road.

At Wingfield House - given this name some time Herbert Lyon had contacted the school -our bus lady supervised our one hour's rest after lunch and we were constantly told to keep still which was imposssible for me owing to my type of cerebral palsey. We were constantly being bullied by the dinner lady, again Mrs. Redford. My mother put cantankerous and odd behaviour down to the fact that she, Mrs. Redford, had a deaf and dumb son, and to the fact that her husband had been killed during the 2nd. World War.

The best part of the school life were the walks in nearby Epping Forest (the resulting nature study lessons and TV programmes, in the main hall, on bird song, made the day bright and cheerful) physiotherapy and speech therapy, and trips to the seaside. We had jars of water life collected from the local ponds, and nurtured our own little individual garden just inside the school grounds next to and at the side of the prefabricated classrooms. Very little in the way of solid lessons can I remember. I particularly remember going by coach with the school to Shoeburyness. We went to this quiet sea-side resort on the East coast of England quite often, during the summer months. Education was not pushed on to us. I learnt very quickly, that I had to teach myself and I eventually took a group in my class for reading although I had a speech impediment.

I can only remember being taught, at Hale End, the times tables, the three Rs, cooking, and a bit of sewing; I made an apron by hand and by the age of nine years I was making a three tiered puffed sleeved floral dress - the school provided the material. I became very proud of my dressmaking achievements and when I visited the school after leaving at the age of nearly eleven years, I made sure I had that dress on, and can remember walking with my head high through the school gates towards the large building, which housed the administrative side of the school.

I feel that the times tables should be taught in all primary schools, which I know at the time of my writing this, they are not. In my daughter's junior school I approached the teacher of her third year class and asked him to introduce the times tables in his curriculum. This he readily did, profusely apologizing to me, blaming the education authority for the inadequacy of the education system of this time. Next time he saw me, he asked me to sit in one of the front desks with the children. He showed me how he had taken my advice and was awarding them a star, just as I had suggested, on the successful completion of each times table. He had pinned each child's results on the classroom wall above his desk. I can remember in my disabled school, where I consequently spent five years of my school life (from the ages of six years to the age of eleven years) the parents gave the classes second hand (usually) goods, such as books, jig-saw puzzles and purses, to be used as prizes for the ones who had obtained the most stars at the end of the week or fortnight. I used to try and learn all the times table all at once!

There is no doubt that my desire to write music came from my father’s side, as well as my mother's side, who were Austrian and the Austrian love for music is well tabulated throughout history as some of the greatest composers were born here.

Bert's project in teaching music to the disabled, which he later perpetuated world wide, is described in detail in later parts of this book

My paternal grandfather intrigued me with the story of his own father which I am excited to relate in the next chapter.....

Chapter 5

My paternal Great Grandfather,

Jeane Baptiste Collier.

Jean Baptiste Collier was a French aristocrat, who spoke many languages, and was a translator and played the violin and wrote music in the French Courts of Phillippe Bonaparte. My paternal grandmother told me when she knew I was writing music;

"You grandfather's father was a very clever man. He spoke languages, wrote music, was translator in the French court of Napoleon the Third and played the violin."

My Grandfather also iterated the same tale, when I was ten. There was some secrecy in the tale, because, I suspect, the French had been hated at the time, and there were dangers and fears of reprisals.

My Grandmother appeared not to like the Frenc. She had been the eldest of eight children and had spent a few months in a convent, being educated to take up employment as a ladies companion. She left the convent before making the grade, but she retained some of that prudish training throughout her whole life. She did become a doctor's receptionist, down Collier Rowe, Romford, for a time.

Alice Dennis lived till she was ninety two years. She died as she lived, a lady. Her breakfast was on the stove; as she died she had put a towel on the kitchen floor of her maisonette in Loughton, Essex, and laid herself out on it straightening out her pinafore and skirts - everything was in order. It was my father's brother's wife who found her that morning as she was the first in, whilst my uncle parking the car. They only came once a fortnight, so this was a strange coincidence I often think about.

As a young man, Jean Baptiste fled to England. He escaped from the French uprising of Met and Paris of 1870, during which the communists destroyed the Granduer of those Cities. Emporer Phillip Bonaparte had restored Paris to the former glory of the King Louis, when he came to power at the beginning of the 1850's.. During that revolution, of 1870, all the arts and theatres and the Palace, were destroyed, never to be rebuilt in that vein again. Thankfully, my great grandfather escaped bringing with him two fortunes, which he lived on. As a young man he cavorted round London with top hat and tails, silver stick and a carnation in his jacket buttonhole.

My grandparents kept a silver framed photograph of him. This picture portrayed an elegant, tall, dark, curly haired and very handsome gentleman with this silver cane, top hat and carnation in his jacket button hole. My grandmother told me he went about London like this, frequenting the high social spots, spending his fortunes. In later life he married and moved to Birmingham. He had a son by this marriage, and named him Henry, my Grandfather.

My grandfather also told me that his father, Jeane Baptiste, had written the chorus tune Tra-Ra-Ra-Boomtie. I did hear once, on the B.B.C, Radio, when I was ten years old, that nobody knew the writer of this tune, which only consists of a few notes. Henry J Sayer put it in his theatre song as interludes between the verses. My grandfather even kept a copy of the music, which I have seen, and which must have been destoyed when my grandmother died. My mother can remember my father's brother holding a piece of paper with music in his hand, when they went to clear out the maisonette aafter Alice's death, but never thought of asking after it ! I am a little upset by this as I would have thought my uncle woul;d have given this piece of music to me knowing that I was a musician.

I have wondered since how much truth is in this story, but somehow I know it must be true, as on one occasion my Grandfather nearly burst a blood vessel when my husband and were taking off the tune outside his bedroom where he kept the piece of hand written music hidden from the family. He had told no one else in the family and I suspect he though we had been in his room riffling through his draws and bedside cabinet which we certainly had not. I use to put my ear to the loud speakers and there heard quite well the radio in this way.

Jean Baptiste married twice. His first wife died when my grandfather, "Harry", was ten years old, and he, himself, died in a French private nursing home in Brighton.

At fourteen, four years after his mother died, and his father had remarried and was producing a second family, my grandfather left his Birmingham home and came to London tofind work.

The Salvation Army took Harry in and helped him to find accommodation. At first, he became a scene shifter at Drury Lane Theatre, and said that while he was working there he had seen the famous clown, Joe Grimaldi. My grandfather then became a French Polisher, and continued to work full-time until he was 80 years of age. I met him and had dinner with him when I obtained employment with Ticko Press head Office situated in the Old Bailey Buildings at Ludgate Hill, in the City of London. We had our dinner in a pub opposite the Old Bailey Court House. He was nearly 80 then.

There is a distant relative in France who writes to my father. He had found him by scouring the telephone directories ion any country he visited; two other families from his branch he discovered were living in Canada and Birmingham. He owns a very well known business in the wine and champainge trade in Chigney les Rose, Riems, France, and his goods are sold all over the world, some bearing the royal crest. His father writes music, which is a strange coincidence and must prove a link with the family. His real name which I cannot reveal hear to protect the family means "Glorious Celebration" in chinese language but the meaning is not found in the French language. There are only four such families bearing that name in the wolrd that can be found. Jeane Jacues has written a song which he published in his firms news sheet, called "Sing a Joyful Song to Champaign". A strange coincidence is that I have recently written a Song of Praise called "Sing to the Lord a Joyful Song, before I knew of the song above!

Jeane Jacques "Collier" writes to my father regularly, before which it had been Charles brother Henry who sadly is now dead, and sends him the company newsletter. The French had a tradition over the centuries of giving their eldest son the same Christian name as their father.

Chaper 6

The Seckers

My maternal grandmother’s family, Secker, (I found my great-grandfather, Evan Secker, mentioned in the 1908 and 1910 Kelly’s book of Records: he was a Station Sergeant in the police, and on retiring became St. Valentines Park Keeper, Ilford) originally came from Austria. Hence my Tyrolean Waltz! So, on both sides of my family I have music origins. One of my cousins on my mother's side, is a director of music for popular groups, and has arranged music for the Royal Variety Shows. The Platters is one of the groups he has directed. Cliff Richard ("That is what friends are for"), Dana ,and Hale and Pace have, all had the benefit of his arranging. He helped out in one of the Royal Variety performances; I believe it was the l996 show.

My mother's father, Albert, was an M.O. and Sergeant Major in the first world war. He also fought as a commando in the Boa War, and won the Comonwealth Medal. He was also awarded medals, and was mentioned in despatches, during the First world war, although he would be the last to admit this, and refused open medal, because;

"My men did as much as me." he said sadly, to his wife, Belinda.

I have a cousin, Captain "Pip" Secker, who served with the Cavalry, during the second world war.

One of my Uncles, my mother's youngest brother, Lord - he used the name George - told me, before he died in l996 at the age of 85, there had been a Clergyman amongst the Seckers somewhere in the past. As the Seckers were an East Anglian family emigrated from Austria some years back in history, I looked in the library for any reference to them. I found my grandfather, Evan Secker, in the Kelly's book of records - he was entered round about the beginning of the l9th century - and a father and son clergyman living in Peterburough, Thomas and Brian Secker. I was tempted to write to them to try and complete the family tree, but somehow I could not bring myself to do so.

Chapter 7

My maternal grandmother.

My maternal Grandmother was forty nine when she gave birth to my mother. Being the eleventh pregnancy, and bearing in mind that Belinda was quite ill at the time having suffered a stroke at the age of forty five - her husband had brought her mouth back to normal with a electric medical appliance he had, which looked something like a light bulb on the end of a torch, along which electric impulses travelled - and had severe bronchitis through smoking and airing damp children's clothing over the stove in the fire grate, which also supplied the room with heat, in the living room. This stovehad to be blacklegged periodically.

Belinda had given birth to four boys and four girls. One boy, James, had died as a baby, in the care of a nanny. He had caught his head in the railings of his cot and consequently accidetly strangled. At this tragic time Belinda and her husband owned a grocers shop plus a dairy, and had the money to hire staff to help out. They vowed they would never hire a nanny again.

Another little girl died at the age of six years. She was my grand parent's eldest daughter, and I have a picture of her, signed by my grandfather, to "Daddy's little Gussie." Gladdis was her name. She died as a result of an attack by a man who had got into her school playground.

The above events and her ill health, all added up to my grandmother not being able to look after her last child, my mother.

My grandfather had always been fighting some war or other, and had not always been around in the upbringing of all his other children. He had suffered shell-shock as a result of his time in the trenches in Flanders, France, during the First Wolrd War; for a while he would forget who he was, and start chasing the family round the house, imagining that they were the enemy Germans.

Albert would make a lot of money at one time, and then go off to fight somebody's war, leaving his wife and children to fend for themselves. On one occasion he did this, my grandmother, Belinda, was so desperate to buy food for her children, that she went down into the cellar of her house beneath her husband's consulting room in Forest Gate, and scraped the barrels of his ointments and filled tins with it, and with a new born baby in arms sold it on a stall down the local market. The tough, weather-beaten "greengrocer" lady, who had the stall beside her was very concerned and told he to go home;

"You shouldn't be standing out here all day by the stall. I am use to it. You are too fragile, and I can see that you have not been brought up to this life. You wont survive it, my dear. So please go home with that young baby there."

On another occasion, Albert bought an exotic looking bird down the local market and on arriving home with it Belinda told him to give it to her. She washed it under the tap and revealed an ordinary canary. Belinda was furious with her husband for allowing himself to be conned. Albert was always feeling sorry for people and must have bought it out of pity for the vendor. He would also spend money on second had cars. The family were among the first to own a car. My mother has a picture of her parents and family (before she was born) taken at a picnic all seated on rugs beside a large open topped car with hood, which was down. Belinda had an expensive looking fur trimmed coat and had on- ths was during their prosperous period.

Belinda had been living on bread and margarine while Albert was abroad fighting, at this time, in order to feed her children; as a consequence her seventh child, but tenth pregnancy, Johnny, was born looking like a scrawny rabbit, and died before starting school, but not before bequeathing his three-wheel bike to his unwanted little newborn sister, whom he thought, on seeing her for the first time, was a china doll and would break. I would like to add, while I am on this tale, that after I married my husband my father-in-law said his mother owned a greengrocery stall down that same market; I often wonder if that sympathetic stall holder had been my husband's grandmother.

"Take it away, I don't want it." Belinda had unimpressively told her husband and stared blankly into space. All her family had left home by now. Valentine was a police inspector with the Met. and Albert, her eldest was a Brethren lay preacher and visited the prisons, including Dartmoor, preaching to the convicts, helping them to rescind their crimes. He was a lovely humble man; I was to meet him and his wife Ida years later - they had no children and lived in Paington, Devon, and were buried there. Uncle Albert would not have a grave headstone. I've seen where he is buried having made inquiries at Singer Oldway House, Paington, Devon.

Belinda still had little Johnny, to care for. She did not want any more. Elizabeth, her surviving daughter was married and had obtained employment as an hotel manageress and also worked as barmaid in a pub in the evenings. Henry, nick named Nobby, Belinda's middle son, was in business as a grocer. "Small profits, quick returns." was one of his saying. Lord, (George) was still comparatively young at twelve years old.

There was nothing that Belinda's husband, or the midwife could do to make her take the baby in her arms. Even the mid-wife's "She will be a blessing in your old age, Belinda. Please accept her." made no difference. Strangely enough, Ivy was the only one who saw her mother in her last few years.

It came to pass that my mother was farmed out to several foster parents, and finally lived with her sister Bessy for a while helping her to look after her four children, one of which became a very successful businessman in Canada. The Eldest lives in Newzealandand sends me a Newzealand Calendar each year. Johnny, Elizabeth's youngest, followed Uncle Albert in his beliefs. He is married with four lovely girls.

Chapter 8

My music

The Carnival March, which I wrote for Wingfield when I was 13, was a novelty piece and Bert asked me to conduct it at every concert - in fact it became the clubs signature tune!. I had streamers and pennies shaken in a bucket etc., to give it atmosphere. Bert had the knack with the performance of my pieces. I also wrote a piece for six instruments (sextet), comprising the following instruments; string quartet, oboe and clarinet. The King’s Men, The Seagulls Flight and Bolero were other pieces of mine. Jena performed a number of my pieces for cello with piano accompaniment, particularly the Seagulls Flight.

I continue to try and write music, with the aid of modern midi equipment.

Chapter 9

Disappointments I Had To Face

I passed an eleven plus type of exam with extremely high marks I had missed the regular exam due to burst appendix, which turned to peritonitis. I nearly died in Queen Elizabeth Hospital, London. My parents were told that it was my fighting spirit which saved me, not the doctors and nurses! I spent weeks in hospital and convalescent home. I hated it in the convalescent home as I was put in a cot in a mixed dormitory with children younger than myself. We had to bath in front of the older boys. When I was told by one of the nurses to turn round and face the boys while I was getting out of the bath, I indignantly defied her and while she was drying me, I bent down and bobbed up and accidentally nearly knocked her out! Serves her right! I had crashed my head under her chin. I did not see her again after that incident.

Essex Education Authority wanted to send me to one of their residential grammar schools, but Bert advised my mother against this. Instead I went to George Gascoigne experimental comprehensive school (previously a Central School) in the next road to where I lived. I was put in the A stream. There were no places at local grammar schools as there were only one or two in Walthamstow at the time and we were part of the baby boom of 1944! They were also too far away for me to travel. A letter from the my head master denying all knowledge that it had been suggested that I go to a grammar school, and said it must have a suggestion by the Spastics Society, now renamed Scope which are now trying to give me some help and support in my later life by visits and helping me to raise some money for a computer in enable me to get more writing done. I thank them for this. My mother had a letter from Essex Education Authority offering a place at one of their residential Grammar Schools North or South of England. Bert Lyon told my mother not to let me go. When Ivy heard that they got the handicapped good jobs counting out screws in factories, she was even more determined not to let me go, even though Dennis Brain's (the famous horn player's) brother taught music in one of the schools.

I also obtained a place at Trinity College of Music, London, Saturday mornings, but Essex would not pay for the grant. The Galbenkien Trust, through Bert and Wingfield, paid instead. I was there until 19 yrs. of age.

I had the qualifications to be a patrol leader with the Methodist Girl Guides, but was told I could not be one because of my disability: I stayed second in command! I was also chosen to be a prefect at school, but was told by the teachers I could not be one because of my disability! This was also the case with the missionary service!

Due to the finality and the dejection it gave to my feelings I was devastingly upset by these rejections and others like these. I was refused entry to a keep fit club for the same reason when I was a child of about seven years, (I had my three wheel bike with me), although my friends had joined. I had a duel handicap; hard of hearing and had cerebral palsy. It was so unfair.

People did not realise how much they had hurt me at the time, and how it would affect my approach to people in my later years - I certainly do not trust anybody. Despite this, I was to receive two top awards. The first one was for being top girl in the borough of Walthamstow, l96l, and the presentation was in the Mayor’s Parlor at the Town Hall, Walthamstow. The second one, - the Gascoigne Award which was the highest honour the school could give to one of it's pupils, - was for being chosen as top girl at the school. Also I was over-all winner of the Singers dress-making competition with a Vogue two piece suit which I modelled.

My school mistress had previously refused to let me take the G.C.E. dressmaking course, although she was taking only one other girl (who was in my class), saying that I was already doing enough! I was studying the following G.C.E.s:- maths, English Language, English Literature, Geography, History, Biology Music, and British Constitrution - I was studying the music G.C.E outside the school with my brilliant composition teacher, Lesley Barnes, who came all the way from Maidavale to teach me, and who later became a concert pianist. I was also learning shorthand and typing with Bert’s dear wife Lily (Auntie Lil), and later on went to evening classes to learn the same. Ironically, she, my dressmaking teacher, who was also Senior Mistress at my school, was sitting in the front row in the audience and I saw her sitting with my maths mistress (who had played my Sea gulls Flight for Violin and piano accompaniment in one of the school concerts) as I walked down the catwalk! What a shockand surprise she must have received, seeing me walk away with the main over-all prize! This prize covered all the sections of the competition.

I found out, years after I had married, that my husband had his weekly piano lesson at Trinity College of Music with my teacher and immediately preceding my lesson.

Chapter 10

Bert Lyon's Views

Bert wanted us girls, in Wingfield, to become good mothers when we married. I always desired, like most women, to have a good husband and father to my children.

The correct discipline of children is very important. I have always felt that school children should be taught how to be parents, not just how to become parents! The schools failure to do this, has contributed to many heartaches and a misconception of married life.

Punishment should be administered with love. Both parents temperaments should be calm and consistent when dealing with their children.

The rod of discipline, mentioned in the Hebrew Scriptures (Old Testament) comes from the Hebrew word meaning shepherds crook. The shepherd uses this rod to guide the sheep gently and firmly, thus stopping them from straying. It is, indeed, a symbol of discipline, administered with love, not brutality and frustration. The sheep would all be scattered if the shepherd used the rod of discipline in this way. Likewise with the family, if the husband or wife is brutal to the children, or each other. Jesus Christ, the great shepherd, gives us the greatest example of how to use this “?rod of correction” in the Greek Scriptures (new testament).

I wish to iterate, that one of Herbert Lyon’s aims was that us girls in Wingfield should marry and prove to be good wives and mothers! I had hoped to achieve this aim.

Chapter 11

Brief story of Janine's brother

Janine's brother Brian was born almost seven years after her birth. Ivy and Charles had waited this long so they could devote all their time to securing a stabilized future for Janine, who was now beginning to learn music and was away at Hale End School during weekdays. Janine was now walking, running and skipping. Janine had taught herself to skip, cycle, and roller skater by great perseverance; many a time she had grazed knees and ended up having to have hospital treatment on them. The scars are still in evidence today.

On one occasion Janine hurtled straight over the handlebars landing on both knees in the gravel in Richmond Road. In later years she ended up falling down

ouble-click to edit text, or drag to move.

Double-click to edit text, or drag to move.

Part 1: 'Riding Life's Storm'

Double-click to edit text, or drag to move.

Double-click to edit text, or drag to move.