The Novel

'Song of theSea'

Spring is Coming,

With it all the hopes and promises

Of a year flourishing,

Frost and snow gone with yester year,

Primroses and the scents of bluebells

In woods will soon be here,

Clear blue skies with pink hues

Will welcome the call of birds

Whose sweet songs

Seem to carry the messages

Of their Creator

Throughout the air,

Wishing us a prosperous and

Happy New Year!

Janet Marie Cattier

Copyright©2014. All rights reserved.

This is the back cover dawn by Janet Cattier

The following intriguing story follows my life as a deaf cerebral palsy girl who found an inner strength to became a normal living citizen. With the help and encouragement of all those round me, especially my wonderful family, I was able to achieve what many normal people would find impossible. It is a biography because it includes the story of the Wingfield Music Club and it's helpers: without these marvellous people I would not be able to tell my story!

Some of the names in this true story have been changed to save embarrassment to the people concerned.

I chose to write part two of my biography in the third person because I wanted to give an overall picture of what it is like living in such circumstances, bringing the people and scenery to life; as if watching a film! Some may say this is confusing. But I have given guides and pictures in the first and third parts which should help to clarify what is happening, and can be used alongside the reading of this nonfictitious novel as a reference. I have called part two a 'novel' in order to be able to give an overall picture of those times.

Oh 'Song of the Sea',

How sweet thou may be,

Stretch out your hand

And reach for me.

The storm now long gone,

So please sing your Song,

Most beautiful and serene.

Chapt 1

Hale End Road School

for the physically disabled

Picture by Racheal, Janet's daughter

.Back and front covers, introduction, and chapter 1 'Hale End Road School for the physically disabled'.

A

B

C.

Copyright©2014. All rights reserved.

2

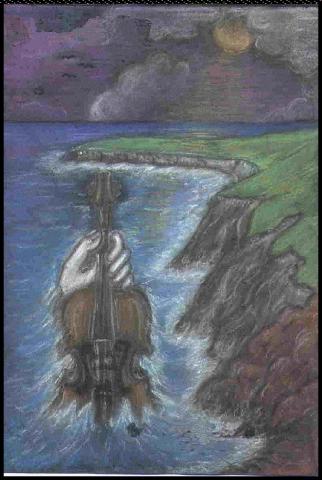

wma music file of 'Song of the Sea'

Click on Cello icon to hear it..

"Good morning children, hope you had a good weekend."

"Yes, Mrs. Hamilton, we did."

"Good. Pauline, it is now your turn to be monitor this month. The register's over there on that table." The slim conscientious teacher in her early thirties watched her class from her spacious desk near the door of the classroom as Pauline pulled out the red A4 sized hard back book, obvious under a pile of papers. Holding a red pencil out to her, she beckoned the beaming girl to sit next to her in the chair on her left.

"Janet Cattier," Pauline recited litigiously, flicking her long brown fringe away from her striking blue eyes.

"Y. y, y, ye!"

The world is now at peace, and the spring month of May AD l952 was no exception to the years that have passed by through the aeons of time. School teachers and their helpers had had their share of the inevitable heartaches caused by the war years. Children have been irretrievably scarred by the evacuation process: being thrown into the unknown, an environment foreign to their proper upbringing, and having 'new values' thrust upon them at such a tender age.

The scents of May wafted through the open windows of the cabin style classroom. The nearby orchard at the back of the school promised much fruit, comprising of plums, damsons, pears, crab apples and blueberries; a wonderful sight this time of year.

After the register was read, Margery Hamilton stepped from behind her desk and started writing on the blackboard, outlining the morning’s lesson which was spelling. But she felt a feeling of resignation today. Her teaching career had been disrupted by seven years of war and its unsettling effects. She had seen many a family change and fall apart owing to the Second World War's torrid impact. She knew that owing to the losses these families have suffered, an attitude of general complacency toward education prevailed, and that she had to do her best with very little resources available. A kindly good looking brunette in her early thirties, wearing a pearl necklace, a neat beige jumper and cardigan, called a twin-set, and brown pleated skirt, Margery knew she was a good teacher and took pride in her work, having willingly accepted this post at Hale End Road Open Air School for sick and physically disabled children, a year ago. She liked her pupils, and took an avid interest in each and every one of them. Her class of eight to ten pupils, being smaller than average, gave her an advantage over her peers in larger 'able-bodied' schools.

Janet, an intelligent sensitive child dressed in a hand-knitted red cardigan, brown lace-up shoes and handmade blue and white checked dress, fully aware of her teacher's pensive mood and intensive stare, was sitting in the second row near the door of the prefabricated classroom which opened onto the concrete playground at the side of the tall grey stoned 'big house'. At that moment, a knock on the classroom door and then the grating sound of the school's wheelchair ramp being put into place against the high step, caused everyone to look expectantly in that direction. Mrs. Hamilton made a move towards the now open classroom door.

"Good morning Mr. Lyon, I have been expecting you. And you are?" Glancing down enquiringly at the boy in the wheelchair.

"Raymond."

"Yes, this is Raymond who is going to demonstrate to your class." Herbert Gascoigne Lyon, a petulant, but cheerful, stocky little man with sleek black hair combed back off the forehead and wearing a black suit, white shirt and tie and shiny black shoes, began pushing the wheelchair holding a young boy who wore iron leg callipers and proudly sporting a brown leather music case on his lap, into the classroom.

It was now the height of the bridging "Spring into Summer" month of May, and the sun shone a welcoming haze through the half open door behind man and boy, sending further waves of scents from the tree blossoms of the nearby orchard throughout the roomy 'army hut' prefabricated classroom. The distinctive sound of a steam train, hooting while it passed along the nearby railway tracks beside the school playground as it approached Walthamstow's Hoe Street station, filled the immediate air waves; distinctive puffs of smoke hurling against the clear blue sky. As if prompted by the train's intrusive sound, Margery Hamilton put down her chalk and with a slight wave of her hand signalled to her class that there would be a change in the course of her lesson. This brought a flurry of activity from her pupils as the previous lesson's writing pads were put away. All eyes were now set in her and Mr. Lyon's direction.

"Quiet children! Allow me to introduce you to Mr. Lyon and young Raymond here," she looked down smiling at the confident wheel chair bound boy. "They have kindly come to give us a recorder recital, and I want you all to listen carefully to what Mr. Lyon has to say to you afterwards about the importance of learning to play a musical instrument and how this will help you. His words could affect all your futures." She spoke instinctively and positively to her class of sick and disabled youngsters, making sure they were paying attention. Her pupils were aged from seven upwards: the policy that determined which class a pupil attended in this school was ability, not age, and her class was intermediate level, meaning that these children were trying hard to learn 'something', despite the sparse resources made available to her. There were hardly any text books in this school.

Janet Cattier and Pauline Carey were the youngest and brightest pupils in her class. They were both nearing eight years old, and had competed with each other since they first attended the class, each asking for arithmetic homework working from donated tattered arithmetic text books. They had found these text books amongst the paraphenalia given by parents to the class as 'prizes' for good behaviour etc, a system introduced by their caring teacher.

Pauline had entered the school a year ago and had proved an above average pupil. Janet arrived eighteen months ago, and had worked her way through two elementary classes where her reading was so good, due to her parents encouragement and elder cousin, Valerie, teaching her from Janet and John books, that she took a group of less able children and helped them with their reading despite her constant stutter. She became very confident, and was consequently put into the third class which was Mrs. Hamilton's.

Janet's mother had only one ante-natal examination, when eight months pregnant, at the Bedford Hospital. After being examined by a female doctor, Dr. King, Ivy Ethel Melinda Cattier was sent home and went into labour a month early, that same night, in the isolated cottage where she had been evacuated during the recent World War with family members of her airman husband, Leonard Charles...

"A month to go, Mrs. Cattier, your baby is doing fine!" Dr. King said putting down her stethoscope, "You can go home now."

Ivy was delighted with this news, but being a nurse there was one thing worrying her. "But doctor, why can I feel a lump under my ribs, surely that must be the baby's head?"

"Baby and you are doing fine. The head is engaged and you have a month to go."

Sweet Ivy, as she was known because of her lovely disposition and kindness. struggled off the doctor's couch. "I must get home, my husband, Len, is waiting for me back at the cottage. He is home on leave for the birth." A shoulder length Brunette, blue eyed Ivy grinned thankfully at the doctor, putting on her imitation leopard skin coat, fondly remembering her wedding day in December nearly two years ago, and made her own way down the corridor and out of the hospital.

Leonard was on leave from war duties for the birth of threir first child and Ivy knew the next time he 'went away' he may not come back: he had already lost his best friend Peter to a 'sniper' plane in an air-raid over Germany. This is why they had tried for this baby.

A jeep was waiting outside the Bedford Hospital from the nearby air-base in Bedford. Roger, an American air-man stationed nearby, had become a friend of the family, and though not particularly good looking was quite a ladies man. He bought them stockings, food and chocolates which were heavily rationed. He was married. But his wife was far away in America and the British girls, married or not, were fair game because of the war shortages. There was a saying amongst the villagers that the American GIs were 'overpaid, oversexed and over here'.

"What did the doc say?" enquired Gloria, Ivy's cousin-in-law, timorously taking a puff on the cigarette supplied by Roger, knowing Ivy did not approve of her relationship with him. Gloria was ravenously dressed in silk stockings and fur coat as it was getting chilly towards the end of November and rather cold for this time of year. She had only recently become close to Roger as she did not know if her husband was going to survive this ghastly conflict with Germany; he was an 'erk' stationed in Egypt and sent home money for her. The cottage was rented by Ernest, Violet's husband. who was also stationed in Egypt.

Closer than was comfortable, thought Ivy, not answering the question.

Gloria was too rapped up in Roger to notice this seemingly snub.

Nothing good can come out of this association; poor Gloria. Ivy was sitting uncomfortably in the back of the open topped jeep while Roger, dressed in his GI uniform, and telling the two women 'to hold on to your hats' started the engine, and roared along the street; she was grateful to be driven home into the arms of Len. Little did they know of the 'storm' that was to follow that night...

While Mr. Lyon was preparing Raymond for his recital and adjusting the music stand, on which he determinedly placed a green recorder book, in front of her desk, Mrs. Hamilton's continued her ruminative mood. She never got tired of marking Janet and Pauline's work: they were meticulously conscientious pupils, and it was purported amongst the school's staff that they could easily pass their eleven plus in a few years time. However, she knew that these two children would be forced to stay at this school until they are fifteen which was the current school leaving age; the eleven plus being deemed unsuitable for them by the Education Authorities.

Janet and Pauline were virtually teaching themselves. They had mastered fractions and were about to tackle decimals, having quickly memorised all their twelve times tables. The rest of the class were just about conquering their two and three times tables, and would not go onto anything difficult until they had done so. She encouraged each child by giving him or her a star for each table they memorised; this star would then be added to a column on a sheet of card with their name at the top, pinned to the classroom wall behind and above her desk for all to see. At the end of a fortnight, each child's column of stars was totted up and the one who had obtained the most received a reward.

The parents donated paraphernalia such as purses, handbags, jigsaw puzzles, scarves, toys, books etc. to use as rewards. At presentation time, the classroom often looked as if the children were about to hold a jumble sale. Janet and Pauline often received rewards for their efforts and good behaviour. Being among her best pupils, of course she was interested in helping them; but she prided herself in taking an avid interest in all her pupils, knowing how difficult it must be for such children.

As an incentive for good behaviour, Mrs. Hamilton also introduced the monitor system in her class. Trusted pupils were set a daily task such as putting the books and blackboard chalk away. There was always an envious atmosphere in her class, and sometimes she thought that she could even be accused of favouritism.

Janet, who held a special place in her teacher's heart because she tried so hard to overcome her difficulties, was a cerebral palsy victim due to the lack of monitoring of her mother's pregnancy during the Second World War: all the best doctors were at 'the front' fighting or attending the injured...

Ivy got home to the isolated cottage in Felmersham and into the arms of Len, leaving Gloria, whose husband was in the middle East with Ernest, Violet's husband. She was oblivious to the sound of the jeep roaring off, with Gloria, into the cold mid afternoon.

"How did it go?" Len asked Ivy attentively, giving her a kiss and a hug'.

Taking off her coat, handing it to her husband, and kicking off her black suede not too high heeled shoes, rubbing her tired feet in the process, Ivy pulled a sad face and told him ruefully, taking his hands in hers: "I don't know Len. Dr. King said I have a month to go, but I am not so sure. I can feel a bulge under my ribs which feels like our baby's head. I am so glad they let you home on leave for the birth." Ivy was intuitive about this and began thinking what her mother, who had died five months ago, would say as she had been a mid-wife. Ivy was the one who found her collapsed due to another stroke in the garden of her home. Ivy's father had been a doctor, but was also deceased

"I would like it to be a boy: I will teach him to play football. But of course I wont mind if it is a little girl, company for you dear," Len said tenderly. He was a good sportsman and a racing cyclist with medals, and mentioned in the newspapers in Cyprus where he was stationed.

"Here's a cup of tea," said Alice, Len's mother, a proud neat fifty nine year old, wearing a wrap round apron, carrying a tray of tea and home made cakes into the lounge from the little kitchen at the back of the cottage. She was preparing the evening meal for the family and the tantalising aroma of beef stew flowed from the open door behind her. The cottage was sparsely furnished and the front room window showed the ample front garden and the lane opposite the field that led down to the river Ouse. "Harry and Vi are out collecting logs for the fire and won't be back for a while. It is rather chilly in here." 'Harry', or Henry, was Alice's husband and a French Polisher by trade.

"In a minute I will do my best with the fire."

"Gloria won't be coming in for dinner, she's staying with Roger," Ivy said, expecting a reaction from Alice.

"She's a silly girl. I feel like writing to Peter and call him home, but she is my brother's child and I am concerned of the trouble this will cause. Perhaps it will fizzle out, after all those yanks are fickle." Alice sighed, guardedly putting the tray on the small wooden table, and poured out the tea from it's floral teapot into a bone china tea cup. "Two sugars," she said robot like, stirring the tea and handing it to a tired looking Ivy. "You need to keep your strength up, dear." Then with the poker in her hand ready to stoke the tired looking fire which crackled slightly, Alice bent down and raked the burning embers in the grate. Then with no further comment, she returned to the welcoming aroma of the scullery. Subject closed. I will hear about the Doc soon enough...

Mrs Hamilton felt sorry for Pauline who had some unexplained physical weakness. She was an extremely well behaved pupil, and a good friend to Janet. All the teacher managed to find out was that her parents had died in a car crash and was now living with her grandparents in one of the Warner flats near Markhouse Road in Walthamstow.

She looked across at thirteen year old Agatha, and there she was sitting at the back of the class with elbows on the table covering her face with her hands, taking no notice of Mr. Lyon and Raymond who were nearly ready to start their recital. Giving the appearance of being extremely unhappy, Agatha had ageing problems and, unfortunately, children were often cruel, calling her Ugly because she took on the appearance of an old woman; she also had an hair lip which did not improve her appearance. Why does she never take off that black belted hooded raincoat.

A few of the other children had "hidden" disabilities, such as diabetes and asthma. This was not the case with hole-in-the-heart girls, Pamela Wells and 'blue baby' Diane Haverly, who were both very weak and not allowed to do much school work; they had a blue tinge to their looks and lips.

To her left was Jennifer in the front row, who did not have long to live. She had no legs, travelling to school with her torso placed in a sturdy plastic shopping bag; she was wedged between table and chair to stop her falling sideways. She inevitably had 'water works trouble' and spent a lot of her time in the welfare department in the 'Big House' across the way opposite this classroom.

Quite an assortment, mused Mrs. Hamilton as she looked at those sad fresh young faces staring expectantly, with the exception of Aggie, at Raymond in his wheelchair who was being handed his maple wood recorder by an ebullient Mr. Lyon. The music stand was set up at the front of the class beside her desk, and the book of music on it.

As a school for the disabled, Hale End was far from equipped for such pupils as Raymond, with stairs in the welfare department and steps to the classrooms. Perhaps this was why he did not attend this school and was probably getting by with home tuition. He certainly had not been seen anywhere in the school. There was no central heating in the 'army hut' prefabricated classrooms, which were heated by an electric bar fire fixed above the door, and on rare occasions a paraffin heater was placed besides the teacher's desk. The toilets were outside next to the 'Big House', partially under cover, and froze during the winter months, making access to them highly dangerous. They were certainly not equipped for wheelchairs.

This large old fashioned building with an imposing flight of large stone steps leading to its front door, was known as the 'Big House' because it had the appearance of a mansion, and housed the administrative, physiotherapy, and welfare facilities of the school. It was formidable and stoical looking, situated about fifty yards from the school entrance. There was a large circular low stone walled garden roundabout between the entrance and this building. Positioned to the right as you came towards the tall building, was the school playground and six twin army-style hut prefabricated classrooms. There were a couple of rooms on its ground level floor which served as a clinic for those in need of medical attention. It also had a basement which housed the cookery classroom and main hall. The dining room was a prefabricated extension to the right from the playground as you came up a slope past the stone steps. The 'Big House' was four storeys high, and the headmaster, Mr. Williams, had his office in the attic and was certainly not accessible to the sick children and he never made an appearance.

At the entrance to the school via the huge wrought iron gates was the large circular flower bed, which also contained bushes and trees. It looked impressive and was used as a roundabout by the school buses to organise the 'coming and going' of the pupils, visitors, and staff.

As the time interval was not long after the Second World War, these conditions in this school were not uncommon to all areas of England, and they certainly existed in many old schools throughout the country. This was the year 1952, during the early stages of the welfare State, and the war had only been over for a period of approximately seven years. The Welfare State was introduced by Attlee's government after their election victory in 1945, in response to the Beveridge Report of 1942. The Welfare State was created by the Labour government to end poverty and look after everyone "from the womb to the tomb" or the "cradle to the grave". Newzealand already had a welfare system set up just before the war in 1938.

In England, the working class were fortunate to have a roof over their heads, especially in London and in the surrounding districts, as the blitz had demolished many dwellings and buildings. Economic and construction recovery was slow. The disabled were fortunate if they had a sprinkling of an education, and many of them did not attend school.

Mrs. Hamilton wondered why Raymond was learning a musical instrument. She also conjectured as to why this little man, of obvious Jewish parentage, was using his spare time to do what others would deem unthinkable, in believing that a disabled child could eventually become a useful citizen in an able-bodied society, and perhaps even work harder than many of those so called 'norms'. Margery had been brought up in a world where many parents kept their "soulful" disabled youngsters away from the prying and cruel eyes of society which could not accept the abnormal. People of all ages poked fun at the disabled, and often parents of the able-bodied encouraged their children in this distasteful and wicked pursuit. Mr. Lyon was proposing to change this attitude through teaching music to disabled youngsters and adults: in doing so, he hoped they would gain self confidence and be able to "hold their own" in this cosmopolitan world. The discipline required in learning an instrument might even eventually equip them for employment.

Despite suffering from the effects of polio which had left the lower half of his body paralysed, Raymond had willingly been taught the recorder by Mr. Lyon who had met him through a neighbour in Belvedere Road, Leyton, where he, Mr. Lyon, lived with his wife Lillian. Polio was rampant around this time.

At last ready for his recorder recital, light brown haired buoyant Raymond, dressed in a green jacked and light brown trousers, put his recorder to his mouth and started to play. Beautiful notes filled the classroom and held the pupils transfixed. Even Agatha took her hands away from her face. His first piece was Green sleeves. The exquisite music flowed ethereally through the air, and when the young musician had finished playing his recitative pieces the class clapped loudly and enthusiastically.

Herbert Gascoigne Lyon came forward, standing upright, folding his arms with a noticeable glint in his eyes. He then addressed the class with an air of strict dignity.

"You lot can play like that," he said in his rather brusque, quick and abrupt voice, unfolding his arms and pointing a forefinger meaningfully at the class. "Raise your hands, please, those of you who would like to learn a musical instrument." There was a show of hands. Encouraged by this obvious interest in his project Mr. Lyon continued his speech rhetorically and enthusiastically. "Mrs. Hamilton and myself are prepared to teach you music free of charge. I shall be holding a class in the main hall across the way from this classroom on Wednesday afternoons from two to three o'clock. Anyone interested can come over and join in, but please ask Mrs. Hamilton first."

"Your headmaster, Mr. Williams, has given me permission to eventually form an orchestra. I have sent out an appeal in the local newspapers, asking if anyone has an instrument that they are not using hidden in their loft or at the back of a cupboard, and if they have, would they kindly consider donating them to this good cause. I shall only be giving the musical instruments to those who have a disability or a health problem. Anyone who is able-bodied who wishes to come along to help or join in will have to provide their own unless they have an extenuating circumstance in that they cannot afford one, or they are a brother or sister of the one who is disabled."

"I have already taught a physically disabled girl, with her left arm missing from below the elbow, to play the cello. She lives round the corner from me. I would like to have your attention for a few more minutes while I tell you her story:"

"I passed this little girl's house one day and found her sitting in the gutter crying. When I asked her why she was so upset, she told me that children had been ridiculing her because she only has one arm. Her parents later told me that she had been born with her left arm missing from the elbow. With their permission I took her into my front room and taught her to read a piece of music. After the lesson, I told her to show those ignorant children the piece of music and ask them if they could read it. They obviously could not read the manuscript and Gina then read it to them. The ploy worked. Those children never bothered her again. She was only six at the time, and I had to have her cello re-strung to enable her to bow the strings with the left arm instead of the traditional right arm. I strapped the bow to her artificial left hand. She has worked very hard and now has an excellent cello teacher by the name of Sylvia. In fact, it is the same tutor who teaches Prince Charles the cello. This little girl has already passed her early grade exams."

"In the meantime, I would like Mrs. Hamilton to instruct you in the theory of music. Would you please ask your parents tonight if they could possibly buy you a recorder and book one recorder tutor the same as this one? Otherwise you will have to wait until we can raise funds for things like this which may take some time." With a wide sweeping gesture of his arm, Mr. Lyon held up a green soft covered book, with a picture of a recorder player on its front cover, for all to see.

"This book is more than adequate to instruct you in the elementary techniques of the recorder."

Turning to Mrs. Hamilton, "I have now got to go and leave this class in your capable hands, and to the children he gave a wave.

The scraping noise of the heavy wooden wheel chair ramp being removed from the step was highly disconcerting to those youngsters with good hearing as it grated and clunked like a mechanical digger. Mr. Lyon and Raymond made their way to the welfare department.

Mrs. Hamilton turned her attention to her class. “That was a very interesting lesson, don't you think? If you ask your mothers and fathers to buy you a recorder and recorder book one this weekend, we shall be able to have music sessions in class, starting on Monday. Some of you will wish to wait until Mr. Lyon raises the funds to buy you one. I will now give you a quick instruction on the structure of a simple musical composition."

"Let us think of the rhythm of a simple nursery rhyme or poem and clap the metre, the emphasis being on the first beat of the bar." Mrs. Hamilton went to the blackboard and wrote out a rhythmic pattern such as this:

Da di di di / da di di di / da di di di / da di di di

Jack and Jill went / up the hill to / fetch a pail of / wa - ter

Da di di di / da di di di / da di di di / da di di di

Jack fell down and /broke his crown and /Jill came tumbling/ af - ter.

The children continued to clap the various rhythms of the nursery rhymes that their teacher recited to them, and she carried on the lesson with this interesting theme for the rest of that day.

The good thing about this school, thought Mrs. Hamilton, is that a teacher does not have to have a set curriculum, but can use his or her own initiative to teach within the capacity of the present pupils. A seven and half year old could be taught cooking and dressmaking. In fact a girl in her class who had cerebral palsy and had great difficulty speaking, walking and using her hands, especially her right hand and arm, was learning to sew properly with fourteen year old pupils, who were in the class next door to her; the lessons were held in the Big House across the way.

This girl, Janet Cattier, wanted to do everything despite the difficulties with her hands. Her right one was virtually paralysed, the arm having the tendency to curl up towards her armpit, taking on the appearance of a bird's wing. In fact, her mother always called it "Janet's little wing". She had struggled to learn knitting, and was now busy making a pair of burgundy coloured moss stitch gloves, having completed elementary items, such as mittens, raffia work, and squares for knitted blankets. Janet let her brain do the work, finding out which movements her arms could do to tackle the various complex tasks in hand. Janet joined the cookery class, again with older girls, and produced such delicacies as cream horns, coconut ice, macaroons, and toffees, as well as learning how to cook a four course meal. She also showed promise at drawing, completing a cartoon page inspired by Key Hole Kate, a character in the Beano Comic. In fact, Janet's health was showing a marked improvement since attending Hale End Open Air School, and this showed in all she did...

Ivy and Len settled down for the evening meal around the square wooden table with the rest of the family. Two year old Valerie, four year old Ken and their mother Vi eagerly joined them: food was short and ration books were relied upon to buy everything. Harry, Len's father, always sat at the top of the table.

"I am going to lie down," Ivy said, pushing her food away, the very smell of it made her want to retch.

Just as she was about to climb the stairs, Ivy fell backward clutching her swollen stomach, "I think baby's coming!" she cried out in pain as her waters broke.

"Quick, Len, go and call the mid-wife, there is a phone down the lane, on the left hand side." Alice and Vi lost no time in helping distressed Ivy to the couch near the front room window.

"Oh dear, we are going to be in trouble, aren't we mum," Vi said in a worried tone. Hope Len gets the midwife here in time."

Len jumped at the command, and grabbing his jacket on the way out he made a dash down the lane, running with all his strength to the telephone. Dialling the number given him, after fumbling nervously with the receiver and the coins, he sighed with relief when the midwife answered. "My wife is in labour a month early," shouted Len down the mouth piece. After giving name and address and getting assurance from nurse Bamford that she would be "there immediately", he slammed down the receiver and ran back to the cottage...

During one lesson, Mrs. Hamilton had severely reprimanded a girl, Rosie, who was a year older than Janet, for using a ruler to construct a drawing when she had specifically told the class not to use one. Rosie had looked frightened of her teacher and had bent her head in shame. For some reason Marjory had taken an unusual dislike to the girl, who was of obvious poor parentage. Rosie's somewhat unkempt appearance was not uncommon at that time as many fathers had died in the war, leaving the mothers struggling to care for their offspring entirely on their own with very little income and virtually no support from the Government. They had to apply to poor relief, which was the remnant of the old system where the poor and sick alike were given the bare necessities of life; a relieving officer gave them a few coppers to buy bread. She could remember a young widow with a daughter the same age as Janet, who lived in a small flat above the laundry near her home, having to sell everything including the lino off the floor in order to buy food. The thoughtful teacher wondered whether the new Welfare State will alter this type of unsavoury predicament in Britain: no sign yet.

Time went by quickly that afternoon. The teacher hoped she had inspired a desire to learn music in her pupils: this was a golden opportunity for them to show that they could make something of themselves, and that disabled need not mean leading hopeless lives. It was pupils like the little 'spastic' girl, Janet, that made a teacher's efforts worth while and it was such a pity that such pupils could not cope with the difficulties present at main stream schools. She had made a point of finding out the reason for Janet's attending her special school. When the little girl first started school at Gamuel Road infants and juniors, she had been excessively bullied outside at home time and had thrice been knocked unconscious in the playground. Janet had been fine during her first year in Miss Titmus' class, but did not have the stamina to withstand the more robust second year in Miss Tobin's class; Miss Tobin also stood in for the head mistress at times. Strangely, Miss Tobin was now teaching here at Hale End and was taking the second infants class in the second twin prefabricated hut situated near the roundabout by the entrance to the school. Mrs. Hamilton wondered why she was teaching here. She had heard that that teacher had not understood Janet at her previous school, and had picked on her there!

"Where is Nurse Bamford?" Len was pacing the room. At that moment there was a knock on the front door and it was the midwife.

She went straight to Ivy who was in pain on the couch, to examine her. "I am extremely sorry, but this is going to be a difficult birth, I wont be able to manage on my own. Will someone call for Dr. Stuart please. And be quick!" The nurse put bowl and towel down and threw her hand across her perspiring brow. I hope he can come. Mother and baby are in terrible danger.

Once again Len ran down the Lane.

"I delivered Gypsy Lee's umpteenth baby this week. I have lost count how many times I've been to her. But I know she drinks raspbery leaf tea and swears by it."

Vi and Alice were comforting Ivy who was still groaning on the couch when Len rushed in through the front door. Ken and Valerie were with Harry in the back room playing drafts: they had to be occupied at a time like this, and knew something wasn't right.

After what seemed to be hours, Dr. Stuart arrived and after examining Ivy he looked concerned, "I cant find the baby's leg and the birth is a breech. I want my partner here, as I cant manage on my own." He looked at Ivy and realised both mother an baby's lives were in danger, especially if Ivy was not strong enough to undergo a difficult birth. She should be in hospital having a Caesarean.

Len ran down the lane to the phone once more, and luckily got Dr. Stuart's partner.

When he arrive, the Doctors' partner found Dr. Stuart holding the baby in his arms, ready to hand her over to nurse Bamford. He was a good gynaecologist though he was noted for his drinking habit.

"I had to work hard to drag the poor baby out. It is an half an hour delayed breech birth with complications. Why the hospital did not see the baby had not turned, I would like to know. A travesty. Oh what a travesty." He turned to Ivy, who had passed out due to the pain. "A good job that mother is strong." he said to his partner. Ivy was a racing cyclist like her husband.

"Why is she black and blue?" Len asked in shock.

"That is bruising. She also has jaundice, unfortunately," Dr. Stuart spoke consolingly to the traumatised family. Turning to a waking Ivy, "Don't worry Mrs.Cattier, you have not got a Chinese baby!" Then the two doctors took their leave, leaving the nurse with Ivy who was oblivious to the sound of the two cars roaring into the cold dark twentieth of November night. Only the antiseptic smell hanging about the room gave any sign they had been there. Nurse Bamford held something up by her hand. "This is the placenta, we call fish and chips," she informed the worried family. Thank the good Lord that this came out whole. Then she handed the baby to a waking Ivy to breast feed.

"We are going to call her Janet Marie," Len told his now wide eyed family...

The shrewd and dedicated teacher felt strongly that there should be proper instruction in subjects such as English language, including spelling, not just the 'three Rs', and regretted that there was an absence of lessons in Maths, Geography, and History. She knew that the whole structure of this school's teaching system was unbalanced, having no GCE exam syllabus. The pupils had to leave when they reached the age of fifteen, and there was no possibility of them entering the eleven plus exam for a grammar school education. But all in all, it was a very good school for those who put themselves out to learn. Sometimes she had only ten pupils under her wing, enabling her to give quality time to each and every one of them.

Janet had raised her hand enthusiastically in response to Mr. Lyon's generous request for pupils to learn the recorder. When the pupils had mastered that instrument, Mr. Lyon hoped they would go on to learn an orchestral one such as a clarinet, violin, trumpet etc. In fact, these instruments would at times have to be adapted in order to suit some disabilities.

The little girl began to feel really excited at the prospect of learning music, for now was her chance to show people she could learn something worthwhile. She was hoping that the awful 'mickey taking' by able-bodied and disabled alike would stop. Yes, some of the disabled children could be just as nasty and unkind to someone who was unbalanced on their legs and who could not hear or speak properly - the fact that she might also be deaf had not yet arisen. Sometimes they could be even more unkind because they were covering up their own inadequacies.

"Get into that classroom, I wont tell you again!" Mrs. Walters, a new teacher in the school had hit Janet on the back of the legs with a ruler for ostensible disobedience on the girl's part when she had not obeyed her command to enter the analogous 'shanty' hut classroom, but had stood all on her own with her back to her teacher staring towards the Big House opposite. Janet sauntered into her classroom crying silently.

Janet was enjoying the view across the playground and had been watching the train pass by the orchard on it's way to London, when she felt the full force of the ruler sharply across the back of her legs. She could hardly speak let alone scream. She began to feel deeply affected by Mrs Walter's treatment of her, not knowing how deaf she was.

In those days, nobody thought of testing children for hearing problems. Bad sight, yes, even though the deaf school was situated at the back of Hale End School for the physically disabled. Also, there were four ESN, educationally subnormal, classes situated in the playground at the back of the disabled school's six huts.

The deaf school was divided from the ESN and physically disabled 'schools' by a high brick wall and two huge imposing iron gates, as if making a loud statement You are a race apart from us! These children made a deafening racket hurrying to the school buses that were waiting in front of the Big House at home time. Their large hearing aid bags and boxes swaying heavily from their bodies.

Owing to the deeply interesting contents of the new subject, music, and the first lesson on musical composition, Janet did not notice the time flying by. She had great difficulty hearing the spoken word and had to rely on lip reading techniques that she had unknowingly taught herself; nobody had suggested that she might be deaf, as she had not had a hearing test. She used her eyes a lot, and the music theory written on Mrs. Hamilton's black board that day, made a lasting impression on her lucid mind. She stuttered a great deal and found it difficult to make people understand what she was saying. Even her own mother had this problem in understanding her speech.

On one occasion, when she was three years old and had just struggled to learn to walk, she had tried to make her mother understand that she wanted the modern looking sandals in a shop window in Hoe Street near the Baker's Arms, instead of the old fashioned white Buck skin ones, bought in Stan Agumbar's shoe shop, that she was made to wear. His shop was situated on the corner of the Bakers Arms just across the road from where she was having this very bad and embarrassing confrontation with her mother.

I want those shoes! Janet continued her frustrated delirium, not being able to speak.

She had not long been walking, and because Ivy could not converse with her daughter to explain the reasons for choosing strongly fitting shoes which were usually lace up, she had felt slighted and threw herself on the pavement screaming. Everybody nearby was looking, probably saying, "What has that mother done to that poor child?" When she could not get her own way she had always jumped in the air, landing on her knees - but this time she also turned on her back, kicking her legs in the air!

She was so disgusted with herself for giving in to her disability that she vowed from that day on she would have more control over herself, and would never let herself make disability an excuse for bad behaviour. She was going to be a person of worth, and not be humiliated by having tantrums, even though she had good reason.

The tune that Raymond played on his recorder was something she could intellectually latch onto, and began to foster in her a desire to play like that.

Janet remembered bending over the old upright piano outside the head mistress' study in Gamuel Road primary school hall, after hearing children play 'Chop Sticks and wanting to learn that tune; she was then in the second class, taken by Miss Tobin, and that was her first school. Now sitting at her desk in Hale End Road, those memories were painful. She'd thrice been knocked unconscious in the school's main playground and shortly after the last fall had staunchly refused to go back, even though Miss Titmus had been very good to her in allowing her to pedal to school on her three wheel 'trike' in her cow-girl costume and tie it up like a horse outside the single ranch style classroom for the youngest children which stood apart from the main building and had it's own little playground. "Anything to get Janet to school!" Miss Titmus told the awkward little girl's perplexed mother. She could not escape the strong feelings of humiliation after going to that piano, and fostered a desire to play like those children.

Oh why was she not able to manipulate her hands on the keyboard like her friends? Her right arm and fingers were paralysed and curled inward. Even her left hand was weak and awkward. The sense of frustration was almost intolerable. Little did she know that the 'tables were about to turn by Mr. Lyon's visit that sunny morning.

Anyhow, now that she was at Hale End Road School, Janet felt that she would not have to suffer any more humiliation or bullying inside and outside school, even at home time. No more would she get set upon outside those horrible prison-like school gates of Gamuel Road primary by nasty gangs of girls hiding on the nearby 'bomb damage' sites.

Every afternoon after school Janet and her friends, the twins Clarine and Claudia who was sometimes called Claudine to rhyme with her sister's name, passed Queen's Road Park near the school. A gang of older girls lay in wait for them on the 'bomb damaged' site, a space where there had been a row of terraced houses before the war, in Longfellow Road next to Queen's Road park. The gang set upon the children as they passed by, calling them obscene names, "Spastic freaks!" they'd call out, throwing bricks and debris left over from the war. On one occasion while Clarine, who was always with her twin - the pair dressed alike - was escorting Janet home from school this gang threw a brick which injured Clarine's head requiring urgent hospital treatment. A kindly man from one of the remaining two houses next to the 'bomb damage' took Clarine, her twin sister and Janet, in his car to Connaught Hospital which was in Oreford Road across Hoe Street, via Queen's Road. Clarine was in great pain and held a scarf to her head to stem the flow of blood.

The fair haired twins were very helpful and full of life. Their mother, who had two other older daughters, Valerie and Wendy, often found the twins a handful because they got themselves into misdirected 'Robin Hood' mischief. When they were very young, Clarine and Claudine would take a family's high quota of milk bottles and distribute them amongst the old ladies they knew, who had and only needed a half pint a day! One could imagine the confusion that followed; people always knew it was the twins doing their 'good deed' for the day! Just think of the frustration this caused their poor mother.

What had happened to Clarine was the deciding factor in Janet leaving Gamuel Road School. Clarine was slightly taller and slimmer than her sister Claudine. Her awful head injury had required several stitches and the incident was all the more horrendous as the real target was Janet to whom those awful kids shouted out:

"Spastic, you should not be on this planet!"

Most of those horrible sad girls lived in prefabs in Longfellow Road where there had been houses before the blitz. Some had lost their fathers during the war, and now their mothers were struggling to care for them. These children were poorly dressed, often having no shoes or underwear, and were jealous of those who were smartly dressed and had fathers. They were also ignorant and played truant from school.

Janet cast her mind back to the time when she was taken by her mother to meet the headmistress of Gamuel Road Infants School to see if she could attend.

"I would like to see how Janet can manage, Mrs. Cattier; yes, we will give her a trial, but please make sure she attends. Janet will be in Miss Titmas' class."

"We will," Ivy said confidently. "I hope starting school later than usual wont hold her back."

"I will make sure that does not happen."

All Janet's friends of the same age group had started the term months ahead of her. Getting bored with the interview, Janet sneaked off unnoticed.

"Where's my daughter?" Ivy looked round to see where Janet was, but she was nowhere to be seen. The head mistress and Ivy went outside into the school playground and heard a lot of laughter coming from the direction of the rabbit hatches.

There was a large gathering of the whole school round those rabbit hutches, and there they found Janet hiding under them appreciative of the astonished audience!

A feature that proved extremely dangerous for Janet in Gamuel Road School was a mound of rubber tyres. left over from the war, placed under a canopy in the school playground. These tyres were accessible to the young pupils who wheeled them at each other. Janet was often bowled over, knocked unconscious, and had had enough. She was now six years old, having just left Miss Titmas's class after a year at the school. She had then refused to go back.

"I am not going to school!" stuttered poor Janet, refusing to get out of bed. I remember too well being accompanied home by nurse on those occasions.

That evening, two days after the assault which she knew was meant for her, while she was being washed down in the tiny living room attached to the scullery of her small terrace at 25 Richmond Road, Walthamstow, her mother, Ivy, had news for her daughter.

"A very kind lady from the Welfare Department came to see me today and asked if you would like to go to another school. She told me that you will be picked up and brought home by a school bus. Miss Barham also said that there are school outings during the summer, and they often visit the seaside."

Janet could remember thinking about the exciting prospect of 'peace at last'. She had nodded in approval. Yes, she would go to that new school, and the thought of not having to suffer being set upon and insulted by those awful gangs of girls in Longfellow Road and Queen's Road Park had pleased her.

"Sticks and stones will break my bones, but names will never hurt me." She hummed to herself the little ditty Ivy taught her just before getting her ready for bed. If any of those gangs attack me, I will sing them that. She found it easier to sing.

I am not going to Gamuel Road School in the morning, she thought happily. The very smell of the place lingered and still made her want to vomit. Certainly not that awful school, she continued humming to herself. She always had difficulty in putting words together owing to the tightness across her chest every time she wanted to speak. Sometimes, she would get angry with herself and beat her chest and stamp her foot, forcing the words out in a continuous stutter.

"Class dismissed," called out Mrs. Hamilton. The school bell was now ringing outside the classrooms in Hale End Road School, bringing Janet back to the present. Mrs. Sangford, the school's kindly middle aged matron, did this ritual before school and at playtimes, every day. It was now time for Mrs. Hamilton's class, after their eventful day, meeting Mr. Lyon, to make their way to their bus for the homeward journey.

.

Introduction

The 2nd World War has now been over for a few years, and the population of the United Kingdom is beginning to settle down to some kind of mundane domestic routine, albeit things would never be the same again as they had existed before the start of the two World Wars. Rebuilding work was slow to start and prefabs were being put up to rehouse the homeless families, of whom many have suffered the loss of a wage earner, who was killed during the war. In fact the whole world has been affected economically and socially; even America had entered the war at the last minute, devastating Japan by dropping the two Atomic bombs on Horishima and Nagasaki due to the "surprise attack" by Japan on it's unsuspecting Pearl Harbour, bringing about an abrupt early end to the continuing conflict; Hitler was already defeated, but the Emperor Hirotito of Japan had refused to give in. Everybody was struggling to survive in this changing world, and as a consequence it was hard for the able-bodied child to adjust, let alone one who was disabled.

The disabled child, at this major critical challenging time in history, was still the most disadvantaged child. No matter what the nature of their disability, they were still being kept away from society, and very often hidden away, as of old, by well meaning parents or guardians. In fact, they were still being treated like lepers by those who should know better in this new so called "New Dawning" civilised society of the 20th Century. This was the sad situation which assailed all disabled children and adults alike even though, ironically, the most well mannered, courteous, and very often the prettiest child was found among this disadvantaged segment of society. The new health service, which came into force at the end of the war, had promised to rectify this gross injustice by making things better for Great Britain's health. In many ways conditions for the pregnant woman as well as general health checks did improve with the introduction of ante-natal care. Also free glasses, dental care, free prescriptions and vitamins, and better hospital care paved the way in lessening the burden of disability and helped to prevent babies being born with defects. Open Air Schools for the sick and physically disabled were now beginning to open throughout the country, offering better health care along with peaceful conditions to ashmatics, polio victims etc. but unfortunately at the expense of a proper all round education including exams, and refusal of entry to the eleven plus.

Organisations such as the Spastic's Society, which is now renamed Scope and is among the largest organisations for the disabled, fought to bring the aforementioned predicament to light. But a lot more was required of individual thinking in kicking away the horror of unjustified prejudices brought about by centuries of ingrained superstitions in that a person was bad if they were born disabled, or their parents had done something to warrent "God's Wrath". Herbert Gascoigne Lyon was the first and foremost of these very farsighted, honest hearted and dedicated people who wanted to change peoples attitudes to the sick and disabled at the cessation of the World War 2. He had an unshakable faith that God was using him to open up the attitudes of people towards the afforementioned and to set a precedent for future societies all over the world.

This intriguing novel is based on a true story of the life of a little girl who came to live on the outskirts of the big city of London who was given the blue print of survival by this unsung hero, "Uncle Bert", as he became known by thousands of disabled children during his very eventful sixty seven years of life on this Earth. He did not set out to be popular and did not care who he upset among the government or medical profession in his quest to further the interest of the disabled or sick child: their aims and desires had become first and foremost in his life. Despite his "take me or leave me" attitude, many people who got to know Bert came to admire the "fire and intensity" that permeated his will, whole personality and drive to further the interests of those worse off than him.