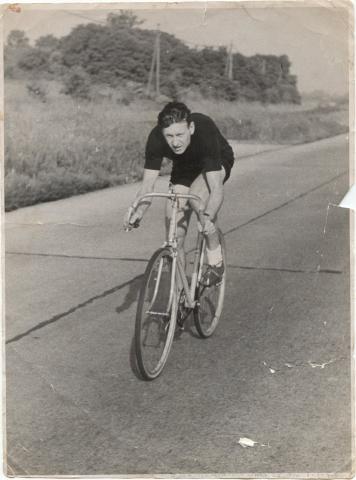

Janet and Sephen's father, Leonard Charles Cattier, training. He was an acclaimed racer in Cyprus during the war; and in England.

Len's Grandfather, Jean Baptiste Cattier, escaped to England with two fortunes and lived the life of a 'toff', frequenting the dance halls and spending his wealth on 'wine women and song'. He wore Top hat and Tails, white gloves and owned a silver cane. Alice had a silver framed photograph of him in her dressing table draw, which she treasured despite her paradoxical hate of French men.

Jean Baptiste wrote the refrain to Henry J Sayer's 'Can Can', which was the song 'Tra, ra ra, Boom de ay'; genetically, is where the nurturing love of music in Janet was blossoming. He could not lay claim to this publicly, for fear of being sent back to Paris - the tale of Two Cities... Alice was so frightened of the consequences, and threatened her husband to keep it a family secret.

Harry, his wife Alice and their three children, rented a flat near London Fields, Hackney. There was another little girl, Gladys, who died during the diphtheria epidemic. The doctor was not able to diagnose her. He thought it was tonsillitis. This was obviously neglect on the doctor's part because diphtheria, as well as TB, was rampant in the thirties in London; he should have warned the heartbroken parents and taken extra precautions and taken a throat swab.

Alice had been beside herself, seeing how ill Gladys was becoming.

"Quick, Harry, go and fetch doctor Brown, Glad is not breathing properly. My gawd, luvas, get him here quickly!" Alice was not that fond of the cockney slang as she had spent time in a nunnery getting 'heducated' to become a lady's maid. She often added an h to words beginning with e as in do you want heggs and bacon for breakfast!

It was Sunday morning and Harry hurried down the tree lined road at his wife's command and banging on the door, he called out to the doctor through the letter box. "My little girl's ill!"

"All right, all right, I will come and see her!" The portly pedantic doctor eventually came out of his house holding his medical bag doing up his jacket, and he and the anxious father hurried along the pavement in total silence. The trees were in full leaf and a few were blooming, giving out exotic scent from pink, white and lilac flowers. Old fashioned gas lights lined the street in between the trees like sentinels. But Harry did not notice, as his mind was on little Glad, his first child.

On entering the flat, the two men found Alice kneeling beside her sick daughter who was lying on the couch. But the doctor diagnosed tonsillitis. This was total neglect on the doctor's part because diphtheria, as well as TB, was rampant during the thirties in London; he should have taken a swab and warned the heartbroken parents and taken extra precautions as it may be diphtheria. Within days little Glad died in her mother's arms. The funeral was a very upsetting occasion for all the family. Alice and Harry went on to three more children, Henry, Violet and Leonard, brining them up in flats.

When the children grew up and left home, Harry and Alice moved in with their daughter Violet and her husband Ernest in Whipps Cross near the Rising Sun pub, not far from the Baker's Arms, Leyton. Then they had to move again. This time to the evacuation cottage rented by Ernest who was in Egypt during the war, outside the small village of Felmersham, Bedfordshire.

One of the reasons that Alice resented moving to Bedford was the lack of medical facilities for her favourite son Leonard's wife, Ivy, when she gave birth to

"Well, dear," Leonard broke into his wife's thoughts, "we have got to give Janet the chance she deserves. My mother turned away my opportunity to learn music. I brought home a violin from school, when we lived in Mare Street, Hackney Downs, and she told me to take it back. It would have cost sixpence a week for the music lessons and my parents could well afford these lessons, but all my mother said was: 'Take that back where it came from, I canno' see why you should want to learn music, it won't get you employment when you leave school!" Alice had visions of her favourite youngest son becoming a Police officer, so music did not fit the bill, and she liked men in uniforms and was courting a policeman before she met her Harry, a very handsome and well turned out young man with lots of mid-blond curly hair.

Leonard's father, Harry, was a French polisher. His, and Janet and Stephen's great-grandfather, Jean Baptiste Cattier, was born in 1826 during the reign of Charles X of France. The Bourbon Monarchy had taken over France after Bonaparte in 1815. King Louis Philippe who took over from King Charles when he abdicated in 1830, fled to England after abdicating in 1848, paving the way for the rulership of the Louis Bonaparte 111, nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte 1, settling in Claremont, Surrey, where he died 1850. 19th Century France was the time of the Bastille, and these times were turbulent and extreme.

Jean Baptiste Cattier was a French aristocrat and translator in the Royal Courts of King Louis Phillippe. He also played the violin and wrote music. He was very young at the time of his escape from Paris.

"He came to England a very young man with two fortunes that he squandered on 'wine women and song'," Alice would eventually tell her granddaughter, Janet. "But he was a very clever young man."

The two previous Kings of France, Charles X and Louis Philippe, had proved ineffective and weak. On becoming Emperor after the worker's uprising of the French workers of 1848-1852, Louis Bonaparte 111 rebuilt Paris, bringing it and the Royal Palace to it's former grandeur. Then the Franco Prussian war broke out in 1872. The Prussians marched through Metz and on reaching Paris, desecrated this beautiful artistic French capital, burning and pillaging, destroying all works of art and books. Consequently, Paris was raised to the ground and France became a Republic.

Janet. Alice thought about the near tragedy during which mother and child nearly died through lack of hospital medical attention. She knew Ivy only had one ante-natal examination, and having been told by female Dr King at the local hospital everything was going well with the pregnancy, had been sent home only to give birth, a very difficult one, that evening a month premature. It was a half an hour delayed breech birth.

Alice had to move from her comfortable home in the roomy terrace house in Whipps Cross where she had the upstairs flat, above, Violet and her two children living on the ground floor, because a bomb had exploded on the air-raid shelter in the back garden, badly damaging the structure of the house.

Very fortunately, and as if by fate, the whole family had decided that night to stay inside the house and not enter the shelter when the sound of the air-raid siren began.

"I’ve had enough of sleeping in the shelter. Let's chance it indoors under the table." So that night, Vi, her two children, Ken and Valerie, who were virtue babies, slept in the dining room with Alice and Harry. That was the only night they had chosen to do so, because Alice had had enough of the damp conditions in the garden shelter and this had saved them all from being killed!

When Ivy and Len bought their present house, 25 Richmond Road, Alice and Harry were invited to come and live with them. Ivy had put a deposit on the house, just beating someone else to it, quick Ivy slammed down a five pound note deposit on the estate agent's table a second before the other person - such was the housing situation in those early post war days when Len was demobbed - after the money came through from her mother's will, her father having died two years previously in a workhouse from Parkinson's disease: Ethel was to ill to look aft him, plus he had suffered from shell shock from the first world war. Ivy had put her name down for a council house but was told that only TB cases rated priority even though she showed them Janet. Apparently, spasticity did not count! Before going to war, the soldiers and air-men were promised houses when the conflict ended, but the Government could not keep its promises. This is why Ivy ended up in one room in Forest Gate after her mother died. She had a nice flat in her mother's house, but was told to move out by her brother, Valentine, in order for the house to be sold and split among the children. Her mother, before she died, had told Ivy, that she could have anything she wished...

"You are the only one who has bothered with me, the others don't even come and see me, I wish they would." Ethel said to Ivy who was pregnant at the time, "You are the only one who looks after me now I am old." Ethel was looking out of the window at her garden in Goldsmith Road Leyton. In the last months of her life her sons and other daughter, Elizabeth, never came to see her. George, her youngest son, was away with the dessert rats driving the lorries in the African Campaign. Her other sons were too old to be enrolled into the forces. Outspoken Violet, Len's sister, wrote to Ivy's brother, Valentine, who was a police inspector in Scotland Yard telling him that this was an awful way to treat his pregnant sister; he had also accused Ivy of stealing a table cloth that had been given to her by her mother as a wedding present.

Ivy's sister, Bessie, even tried to stop her getting anything from their mother's will by spreading it around that as a baby Ivy had been bought from the 'Lemon Lady', who sold lemons from a stall in the local market, knowing full well that this was an untrue and stupid story! Fortunately, the clause in the present Will, 'Everything I own is to be split equally among my children and any who should

Chapter 3

Janet and Stephen's Grandparents, Harry and Alice Cattier.

Janet and Stephen were now safely tucked up in bed. It was 8.30pm and the day's 'notorious' events with Mrs. Redford still festered in Janet's mind, putting a damper on Mr Lyon's visit that week.

Ivy put Prudence, their black and white three month old kitten, out the back door. She now had a couple of hours before their father arrived from his evening lecturing job. After changing out of her old skirt and jumper into a blue and orange sleeveless dress that became her trim figure and combing her delicately permed shoulder length medium brown hair, she now had time to relax and knit, her fore fingers flying over the needles which she held professionally in the crevice between first finger and thumb of both hands, the beige and red wool quickly disappearing from the two large balls that she had earlier wound by hand. Her mother-in-law, Alice, often helped by holding the strands over both hands, with arms opened outward and wide. Alice always said the Lord's prayer in bed every night: Ivy listened at her in-law's bedroom door on the right of the three foot square landing at the top of the stairs!

Ivy was quick and deft in everything: she had not been known as 'flit' in school for nothing! The fair-Isle pullover she was knitting Leonard was steadily growing and would soon be finished. She was sitting in the small dining room on the little orange 'put-u-up' which was placed against the wall where the stairs ran up the middle of the small terrace house, dividing the front and the back. There was a cupboard under the stars and sideboard in the recess to her right. She prided herself in not being a 'piffle' person and was extremely house proud. So was Alice, a staunch Christian who lived with husband Harry in the front half of the house. They helped with the mortgage repayments, as Len did not earn a lot. Ivy had taken over the finances when Len had forgotten to pay the mortgage.

"Len, we've just had a final warning of repossession from the bank. From now on I handle the finances." Ivy knew that he did not like queueing up at banks, especially during his short lunch break and he often worked Saturdays. Fortunately, Len agreed, and had carried on reading his newspaper that was delivered earlier that day: he was contented with his hard working happy married life and had decorated the dining room to Ivy's taste. But Ivy had shown her frustration by going into the scullery without another word to finish her baking, later gathering the money together with help from Alice, which she paid into the bank the next day. The bank manager had been very understanding.

Baby Stephen had been restless all day, due to the unusually hot May weather and to teething, so she badly needed to unwind in order to be ready for her hard working husband to appear with his bicycle out of the narrow passageway to he left, adjacent to next door's hall. The flowers in their little garden were blooming; little 'applets' were forming in place of the blossom on the bramley apple tree at the bottom of the garden, promising a bumper crop this year. Ivy looked forward to devoting more time to making apple pies, a favourite of the family.

At last, she heard a welcoming call "Hi dear" from the long narrow hallway. It was ten thirty and after helping him through the door into the living room, Ivy was not looking forward to speaking about the day's events so late in the evening. After he brought his push-bike through to the back door in the scullery, putting it away in the garden under the canopy opposite, fixed to the fence dividing next door, Len pulled off his sweaty jumper. He sat down in the small dining room attached to the scullery. sniffing the aroma of his long awaited meal. which was beef hotpot. With a serious expression, and gesture of her hand she handed him his cup of tea and then put his dinner on the table in front of the sashed window overlooking the small narrow garden, the outside toilet visible to the left between the scullery and the shed; it was integrated with the house. Government bathroom grants were becoming available and Len and Ivy were thinking of applying for one: they used a copper to heat up the water and a tin bath hung under the garden canopy which stretched to the end of the narrow scullery.

"I had an interesting day dear." Len said as he sat next to Ivy after he'd eaten and taken the plate out to be washed up, and placed the floral bone china cup and saucer on the flap down table by the window. He related to his wife the happenings in work that day, and about the students at the London School of Printing, which was based at the Elephant and Castle, London, where he lectured in the evenings. His day job in Aldgate, London, was with a printing firm where he printed out books and Vogue pattern covers; he also did prints for the London Museum of very old paintings that were too fragile to put on show. He kissed Ivy and asked after her day.

They agreed to buy Janet the requested recorder and tutoring book, and agreed it would not be a waste of money as their little girl needed all the encouragement they could give her. Ivy then reluctantly told her tired husband how Mrs Redford had behaved in terrorising their daughter that day.

"Don't you worry about that awful woman," Len spoke consolingly, reiterating, "Let me know if there are any more developments." He was tired and longed for his bed and sleep to descend upon him, but pleased at his daughter's progress in school. He was a dark haired five foot ten, handsome athletic looking man who love sport, especially cycling. Janet had a space between her top front teeth just like he had, and an old wives tale said that this was supposed to bring luck! She was certainly her father's daughter: she loved the outdoor life.

"I will take Janet to that music shop, Savilles, in Hoe street near The Bell, on Saturday morning, but I shall have to take Stephen with me, as you are doing overtime this week." Ivy said thoughtfully, glancing around at the cream coloured silver squared patterned wall paper Len had not long put up, remembering the time as a little girl when she desired to learn the piano like her elder sister, Elizabeth. Bessie, being their parent's fourth child and only girl at the tine, had the advantage of their father's total attention. They did have another little girl named Gertrude, who died after being attacked in a school playground, at six years old, by a man who scaled the high wall. It had been a sexual assault. Ivy treasured the picture of her sister she never me. Gussie had long dark ringlets down to her waist and wore the apron style dress of those times. It had written on the back, 'Daddy's little Gussie'. Very very sad, thought Ivy. Their second child, James, died when the nanny left him in his cot and he accidentally caught his head between the railings. Ivy's mother, Ethel, refused to have another nanny, deciding to look after the children herself. She had eleven, Ivy being the youngest, but only six survived into adulthood: it was survival of the fittest in those days. Ivy wondered if they would have been taught music, thus gleaning the advantage of her parent's wealthy days. Ethel and William had owned a Dairy and then a shop in Little Ilford, and of course he, being a medical man, had his surgery with a plaque on the door, reading: 'Herbalist and Skin Specialist', in Atherton Road, Forest Gate, and then Goldsmith Road, Leyton. He was also the local dentist. In those days Ethel and William Flay could well afford to educate all their children with the exception of Ivy, who was fostered because of Ethel's ill health and age: Ivy was their eleventh. Baby Ivy's second foster mother had a piano and was going to have her taught but unfortunately died of TB and little Ivy had to be moved on again. Ivy did not let the whole episode of her growing up interfere with her own family's plans. Ivy's elder brother, Valentine Flay, was the youngest inspector to enter the Metropolitan's Scotland Yard.

be born to me hereafter', still stood.

Her brothers and sister's lack of concern for her could have embittered gentle Ivy, but it did not. There may have been another will, hidden in her mother's huge locked dresser, that may have written just before she died, and which could have allowed Ivy to stay in the house while she needed to. Honest Ivy could not bring herself to open the dresser, even though she knew that the key was in her dead mother's apron pocket. Valentine got to the dresser and had obviously found the new will and tore it up. Ivy was once again rejected by her family in an awful way. Fancy threatening to send the CID down to his pregnant sister if Ivy touched anything. Valentine laid claim to that dresser...

After laying out her mother on the couch by the window in the front room, Ivy slept in the house on her own and was frightened by the large spider suspending itself on it's web above her head as she lay in bed. Ivy thought, Pregnant woman shouldn't have to do all this, or have any frights! Being a trained nurse I know this. I love my mother and would have done anything for her, even though she did not want me. Ethel was short, stubby and was a midwife. The midwife that delivered Ivy had told Ethel that this baby would be a blessing in her old age, and this had proven true.

During that night, Leonard came home on leave from the Royal Air-Force. He did not want to disturb his mother-in-law and Ivy. Finding the house in darkness, he looked around. The basement window was locked. Then he looked upwards and all the windows at the top were shut and curtains drawn. Mr Gray and the old German woman, Ethel's lodgers who had the top rooms in the house, would be sound asleep. Then he spied a front room bay window slightly open. He thought this strange. He put his air-force cap into his grey uniform pocket, and went up the large stone steps to the front door. He leaned over the basement iron railing to reach for the window and managed to prise it open. He climbed onto the railing and lifted himself upward and through the window, landing on the couch on top of Ethel's body, which had been laid out by his pregnant wife and left in the front room on the couch underneath the window. To his horror it felt cold and he rolled onto the floor. Switching on the light, he saw Elthel's white face and sightless eyes staring up at the the ceiling. Surely, she's not...At least I am here to help with the funeral arrangements, although his Ivy would have to do all the running about to see to the insurance, etc...

While Len was discussing with Ivy the prospect of buying Janet the recorder and recorder book, Janet's grandparents were having their supper in the front room. Ivy hardly saw them owing to the design of the house. Though small and terraced, the little houses in her road were often divided between two families to help with the mortgage or rent. The Range's house, next door, had the owner, an elderly man in his early eighties, Mr. Nointing, living in the front room while his tenants had the run of house.

On rare occasions, when Janet had been flung into the hall by her mother for being naughty, 'Nanny', Alice, would come out and take the screaming girl into her beautifully laid out front room. Consoled, she would stop her tantrum, much to the disgust and consternation of her mother. Many a row was caused by Alice's interference.

Janet hardly slept that night, busy thinking about learning music and hoping her parents would agree to buy the recorder and book that weekend.

Friday morning eventually materialized and she was glad when her mother came into her room to wake her for breakfast in time to get ready for school. The time was now seven o'clock, and her father had just gone out of the front door with his bike, on his way to work.

Len was a keen cyclist and nearly every Sunday morning he trained at North Weald in Essex for the cycle races. He always got up very early; it seemed about 2 O'clock in the morning to Janet. When she was small, Ivy often took her in the seat on the back of her bike to meet him later during the morning, then on returning home, after dinner, it was Sunday school for her. The Cattiers were a very active family and extremely close. Leonard also went swimming, boxing and played in a football team in Leyton where he was a reserve for division team Leyton Orient, although he gave up some of these pursuits as time went on in order to devote more time to his family. But he still went to his cycling club.

On one occasion, when work mate Tom Marsh and his wife, Dolly, visited them, Tom sent his son Alex up to Ivy and Len's bedroom as a punishment, and there he stayed until Janet came home from St. Barnabas Sunday School;

"You won't go with Janet to Sunday School? Right, then you will not do anything else until she get's back." The crying and dazed boy was sent up those steep stairs that ran up the middle of Janet's house. His sister, Linda, was only toddling at the time, and wondered what all the fuss was about.

Ivy sometimes left the children with Alice and Harry when she met her husband after his early morning training with his cycling club. She belonged to the Free Wheelers cycling club where she used to take her daughter for an airing when Len had previously been so engrossed in his sporting activities. Sometimes it would be a boxing match, or football match, or a swimming and cycling event. They both knew that Janet would never be able to follow in their footsteps. Leonard hoped his son, Stephen, would show promise in these pursuits. He always wanted a boy, and now he had one he was a very contented man. He was very happy with Ivy, as she was proving to be a very shrewd housewife. Owing to his worries over Janet, and the trauma of losing some very good Royal Air Force friends during the war, including his best friend, Stephen, he had forgotten to pay the mortgage on a few occasions. This was not surprising with all the extra work he was doing to keep his family in some style. He also did not like queues, authorities, or banks! Fortunately, Ivy found a reminder from the Halifax Building Society and took over the mortgage repayments. Yes, she was an excellent manager.

It was their interest in cycling that was one of the attractions bringing them together. They met just before the outbreak of the second world war while he was an Air Cadet and played the principle trumpet parts in the cadet band. He was just beginning to learn proper music and had been given a piccolo, when he was posted overseas and into the war.

Before Alice and Harry moved up to London to live with them, Ivy often took Janet, in the back seat of her cycle, to see the family she had left behind in Bedford. Ivy had left the cottage while her handicapped daughter was still a baby because she had to find accommodation for herself and Len to get it ready for when he was demobbed and looking for work. His Litho printing work was in London and he had to finish his apprenticeship in Lithographic Printing which was a seven year evening class and day course. Also, an unfortunate incident which she did not want to dwell on at this time occurred, disrupting the happy family atmosphere in that cottage in Bedford. Anyhow, that is the story she told. The true story was not to be told many many years later, on the death of Gloria, Len and Violet's cousin.

After her father was demobbed, Janet did not want or indeed recognise him as he had been away so long. Because she had not known him, Janet had taken to his sister's husband, Ernest, and thought of him as her father. "Baggor! Angor! Go away!" she stuttered when he came home from work, and kicked the wheel of his bike as she hid under the dining room table. Leonard had to bring his bike through the house to store it in the back garden, under the canopy which was attached to the fence just outside the dining room and opposite the scullery door. He had built this bike out of spare parts from Lipscombes' Cycle shop in Markhouse Road, Walthamstow, and was very proud of it, and now it was being kicked by his irate stranger of a daughter: Jan had accepted Violets husband Earnest as her surrogate father and did not want another one, especially a complete stranger. Yes, Earnest came back from he war earl, with Peter, Gloria's husband to sort out the American GI affair.

Not long after this, Len made a seat on the back of his bike to give Ivy a break from the burden of having Janet on the back of hers. His ungrateful daughter did not like this seat her father had painstakingly made, and screamed all the way along the roads until an infuriated and frustrated Len stopped and, taking the seat off his bike, he threw it in a sad rage onto a nearby bomb damage site. "That is the last time I do anything for that girl!" he bemoaned beside the road, with his head in his hands. Ivy had to coax her husband to get on his bike and return home!

Janet did not begin to take her first unsteady steps before she was two and a half years old, and sometimes on the trips to Bedford she would plan to run away across the fields opposite the cottages in Felmersham towards the River Ouse. Her grandmother was often seen running in close proximity behind her during the family's visits!

After breakfast that Friday morning, the school bus arrived much earlier than usual. The bus was almost full and Mrs. Redford gave a wide smile instead of her rather hostile sullen look on opening the bus door to Janet and her mother. The turbaned bus lady did something she had never done before, helped Janet onto the bottle green mini bus. onald gave a wry smile bemused at the thought of this tyrant havinmg met her match in the little spastic girl's mother, Ivy Cattier.

“That woman had better not bully her ever again," thought Ivy as she waved her daughter goodbye.

On the arrival home, that night, Mrs. Redford did not mimic Janet's awkward wave, and was determined not to give the slightest excuse to be reported to her local education authority, especially not the LCC, London County Council.

Janet began to notice Mrs. Redford’s change of demeanour towards her, and felt awkward and uncomfortable in the bus lady's

presence. In fact, she now left Janet alone but unfortunately found another child on whom to vent her frustrations! It was a 'snotty' nose boy, Grant, who was in the same class as Janet.

"Don't you ever bring a handkerchief, and for a goodness sake walk properly and not talk so loud!" She shouted, pushing and shoving the frightened lad as he got onto the bus and sidled reluctantly past her. Donald shoook his head sadly, and Janet had never seen Grant look so unhappy and scared.

At Hale End, every youngster in the three lower classes - there were five in all, the sixth one being used as a storage room - had to take one hour rest in the main hall every day. The beds were laid out side by side, and Mrs. Redford was extra vicious to children who fidgeted and turned onto their side or stomach. She would stalk over and rip the blanket off them and force them to exchange beds for ones closer to where she sat knitting. She made endless jumpers, pullovers and pairs of socks, for her son John, at the school. She would even knit on the bus! The paradox was that if any child fell asleep, she would leave them there all afternoon while she sat knitting whilst watching over them; especially Janet and Sandra Nevill.. Poor Sandra often got the blanket whipped off her for scratching her eczema. These beds were sometime's laid out in he playground during the summer but were then overseen by Mrs. Sandford, the school's kindly middle aged house mother.

Janet could not wait to get into the next class where she would be free during lunch times, and was working extra hard teaching herself maths and competing with Pauline Carey who was due to 'go up' next month as she was the eldest of the two girls. She wanted to play in the playground with the older and fitter children after dinner.

Janet had picked up every childhood illness, and measles had left her screaming with abscesses in both ears; this was the time at the end of the war when Ivy lived in one room in Forest Gate. The land lady suffered with St. Vitus' dance and was extremely dirty. One day, Ivy picked the hall carpet up to shake out the dust, but it literally fell apart!

Due to Mrs. Redford's artificial behaviour in being over nice to her, having been so sadistic, Janet started to feel very embarrassed in her presence and did her best to avoid talking to her, during which she stuttered uncontrollably from that day on. This could have a long term effect on her if she did not put Mrs. Redford's odd demeanour in the right perspective and get the woman off her mind.

Ivy told her rather confused daughter this Friday evening that her father had agreed she could have a recorder. She was to take her to Saville's music shop in Hoe Street next morning, Saturday, with baby Stephen strapped in his push chair. Janet's brother loved his outings, especially when he was taken near the railway bridge in Queen's Road. He could only say a few words, but made his excitement plain when he heard the sound of a train rattling and hooting in the distance! Ivy could never get past the bridge without showing him the trains and waiting for one.

Double-click to edit text, or drag to move.

Fin editing